(Last revised: March 2025. See changelog at the bottom.)

13.1 Post summary / Table of contents

Part of the “Intro to brain-like-AGI safety” post series.

In the previous post, I proposed that one path forward for AGI safety involves reverse-engineering human social instincts—the innate reactions in the Steering Subsystem (hypothalamus and brainstem) that contribute to human social behavior and moral intuitions. This post will go through some examples of how human social instincts might work.

My intention is not to offer complete and accurate descriptions of human social instinct algorithms, but rather to gesture at the kinds of algorithms that a reverse-engineering project should be looking for.

(Note: Since first writing this post, I think I've made good progress on this reverse-engineering project! See especially A theory of laughter and Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch. There’s still tons more work to do, of course. This post will not discuss those later developments, but rather explain and motivate the basic problem.)

This post, like Posts #2–#7 but unlike the rest of the series, is pure neuroscience, with almost no mention of AGI besides here and the conclusion.

Table of contents:

- Section 13.2 explains, first, why I expect to find innate, genetically-hardwired, social instinct circuits in the hypothalamus and/or brainstem, and second, why evolution had to solve a tricky puzzle when designing these circuits. Specifically, these circuits have to solve a “symbol grounding problem”, by taking the symbols in a learned-from-scratch world-model, and somehow connecting them to the appropriate social reactions.

- Section 13.3 and 13.4 go through two relatively simple examples where I attempt to explain recognizable social behaviors in terms of innate reaction circuits: filial imprinting in Section 13.3, and fear-of-strangers in Section 13.4.

- Section 13.5 discusses an additional ingredient that I suspect plays an important role in many social instincts, which I call “transient empathetic simulations”. This mechanism enables reactions where recognizing or expecting a feeling in someone else triggers a “response feeling” in oneself—for example, if I notice that my rival is suffering, it triggers the warm feelings of schadenfreude. To be clear, “transient empathetic simulations” have little in common with how the word “empathy” is used normally; “transient empathetic simulations” are fast and involuntary, and are involved in both prosocial and antisocial emotions.

- Section 13.6 wraps up with a plea for researchers to figure out exactly how human social instincts work, ASAP. I will have a longer wish-list of research directions in Post #15, but I want to emphasize this one right now, as it seems particularly impactful and tractable. If you (or your lab) are in a good position to make progress but would need funding, email me and I’ll keep you in the loop about possible upcoming opportunities.

13.2 What are we trying to explain and why is it tricky?

13.2.1 Claim 1: Social instincts arise from genetically-hardcoded circuitry in the Steering Subsystem (hypothalamus & brainstem)

I want us to have a concrete example in mind going forward, so I’ll focus on a particular innate drive that I’m quite sure exists. I call it the “drive to feel liked / admired”—see my post Valence & Liking / Admiring.[1] This is the near-universal desire to feel liked / admired, especially by those whom we like / admire in turn, and whom we see as important. This desire is closely related to the human tendency to seek prestige and status, although it’s not exactly the same (see my two-part series on social status phenomena here & here).

(Remember, the point of this post is that I want to understand human social instincts in general. I don’t necessarily want AGIs to exhibit status-seeking behavior in particular! See previous post, Section 12.4.3.)

My claim is: there needs to be genetically-hardcoded circuitry in the Steering Subsystem—a.k.a. an “innate reaction”—which gives rise to this desire to feel liked / admired.

Why do I think that? A few reasons (see also my similar discussion in Section 4.4.1 here):

First, a drive to feel liked / admired would seem to have a solid evolutionary justification. After all, if people like / admire me, then they tend to defer to my preferences, plans, and ideas, including helping me when they can, for reasons described in Section 4.6 here. Relatedly, I’m not an expert, but I understand that the most liked / admired members of hunter-gatherer tribes tended to become leaders, eat better food, have more children, and so on.

Second, the drive to feel liked / admired seems to be innate, not learned. For example:

- I think parents will agree that children crave respect / admiration starting from a remarkably young age, and in situations where those cravings have no discernable direct downstream impact on their life.

- Even adults crave admiration in a way that’s rather divorced from direct downstream impact—for example, I would react much more positively to news that Tom Hanks secretly thinks highly of me, than to news that some obscure government bureaucrat secretly thinks highly of me, even if the obscure government bureaucrat was in fact much better-positioned than Tom Hanks to advance my life goals as a result.

- The desire to feel liked / admired is (I think) a cross-cultural universal…

- …But simultaneously, that same desire seems to have a lot of person-to-person variation, including being apparently essentially absent in some psychopaths (see discussion of the “pity play” in Section 4.4.1 here). This kind of inter-individual variation seems to better match what I expect from an innate drive (e.g. some people are much more sensitive to pain or hunger than others) than what I expect from a learned strategy (e.g. pretty much everyone makes use of their fingernails when scratching an itch).

- There may also be an analogous drive to feel liked / admired in certain non-human animals, like the Arabian babbler bird.[2]

In my framework (see Posts #2–#3), the only way to build this kind of innate reaction is to hardwire specific circuitry into the Steering Subsystem. As a (non-social) example of how I expect this kind of innate reaction to be physically configured in the brain (if I understand correctly, see detailed discussion in this other post I wrote), there’s a discrete population of neurons in the hypothalamus which seems to implement the following behavior: “If I’m under-nourished, do the following tasks: (1) emit a hunger sensation, (2) start rewarding the cortex for getting food, (3) reduce fertility, (4) reduce growth, (5) reduce pain sensitivity, etc.”. There seems to be a neat and plausible story of what this population of hypothalamic neurons is doing, how it's doing it, and why. I expect that there are analogous little circuits (perhaps also in the hypothalamus, or maybe somewhere in the brainstem) that underlie things like “the drive to feel liked / admired”, and I’d like to know exactly what they are and how they work, at the algorithm level.

Third, I claim that rodent studies have clearly established that innate social reactions can be orchestrated by groups of neurons in the Steering Subsystem (especially hypothalamus) can orchestrate innate social reactions and drives—a few examples are in this footnote[3]. That should make it feel more plausible that maybe all innate social reactions are like that, and that maybe this is true in humans too. I wish the literature on this topic was better—but alas, in social neuroscience, just like in non-social neuroscience, the Steering Subsystem (hypothalamus and brainstem) is (regrettably) neglected and dismissed in comparison to the cortex.[4]

13.2.2 Claim 2: Social instincts are tricky because of the “symbol grounding problem”

For social instincts to have the effects that evolution “wants” them to have, they need to interface with our conceptual understanding of the world—i.e., with our learned-from-scratch world-model, which is a huge (probably multi-gigabyte) complicated unlabeled data structure in our brain.

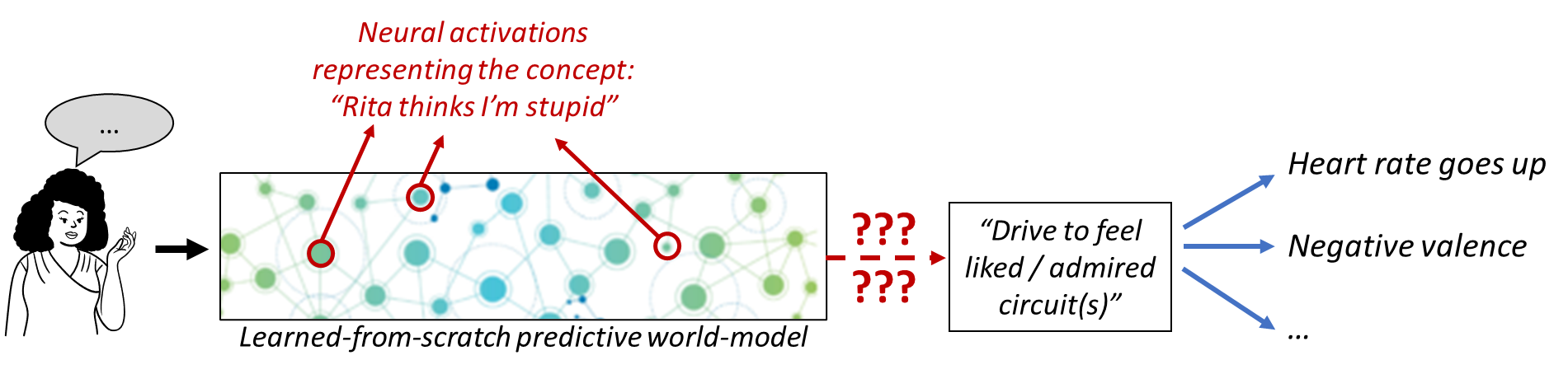

So suppose my acquaintance Rita just said something about politics that seems to imply that she thinks I’m stupid. My understanding of Rita and her utterance is represented by some specific neuron firing pattern in the learned cortical world model, and that’s supposed to trigger the hard-coded “drive to feel liked / admired” circuit in my hypothalamus or brainstem. How does that work?

You can’t just say “The genome wires these particular neurons to the innate drive circuit,” because we need to explain how. Recall from Post #2 that all my concepts related to Rita, politics, grammar, conversational implicatures, and so on, were learned within my lifetime, basically by cataloging patterns in my sensory inputs, and then patterns in the patterns, etc.—see predictive learning of sensory inputs in Post #4. How does the genome know that this particular set of neurons should trigger the “drive to feel liked / admired” circuit?

By the same token, you can’t just say “A within-lifetime learning algorithm will figure out the connection”; we would also need to specify how the brain calculates a “ground truth” signal (e.g. supervisory signals, error signals, reward signals, etc.) which can steer this learning algorithm.

Thus, the challenge of implementing the “drive to feel liked / admired” (and other social instincts) amounts to a kind of symbol grounding problem—we have lots of “symbols” (concepts in our learned-from-scratch predictive world-model), and the Steering Subsystem needs a way to “ground” them, at least well enough to extract what social instincts they should evoke.

So how do the social instinct circuits solve that symbol grounding problem? One possible answer is: “Sorry Steve, but there’s no possible solution, and therefore we should reject learning-from-scratch and all the other baloney in Posts #2–#7.” Yup, I admit it, that’s a possible answer! But I don’t think it’s right.

While I don’t have any great, well-researched answers, I do have some ideas of what the answer should generally look like, and the rest of the post is my attempt to gesture in that direction.

13.2.3 Reminder of brain model, from previous posts

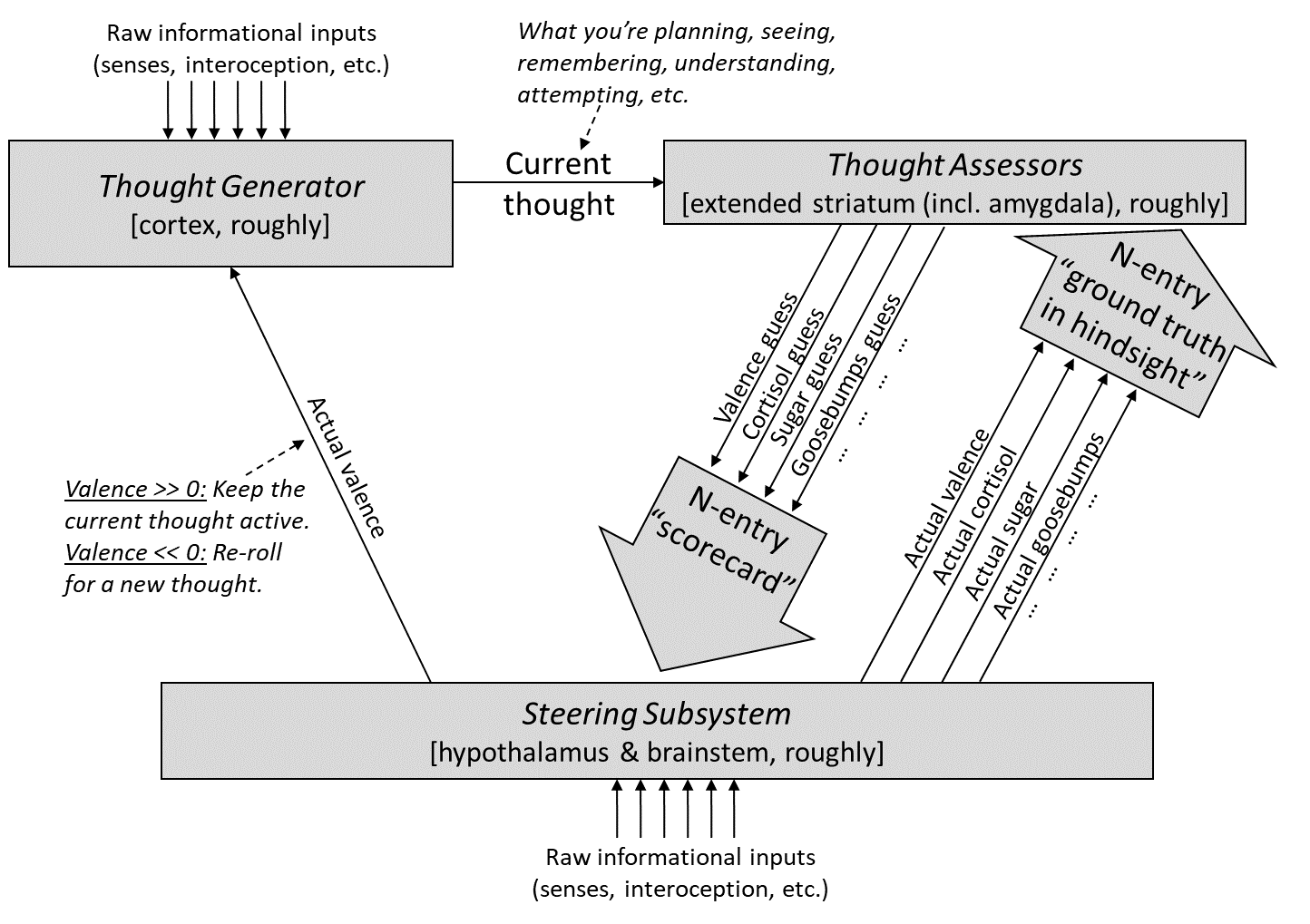

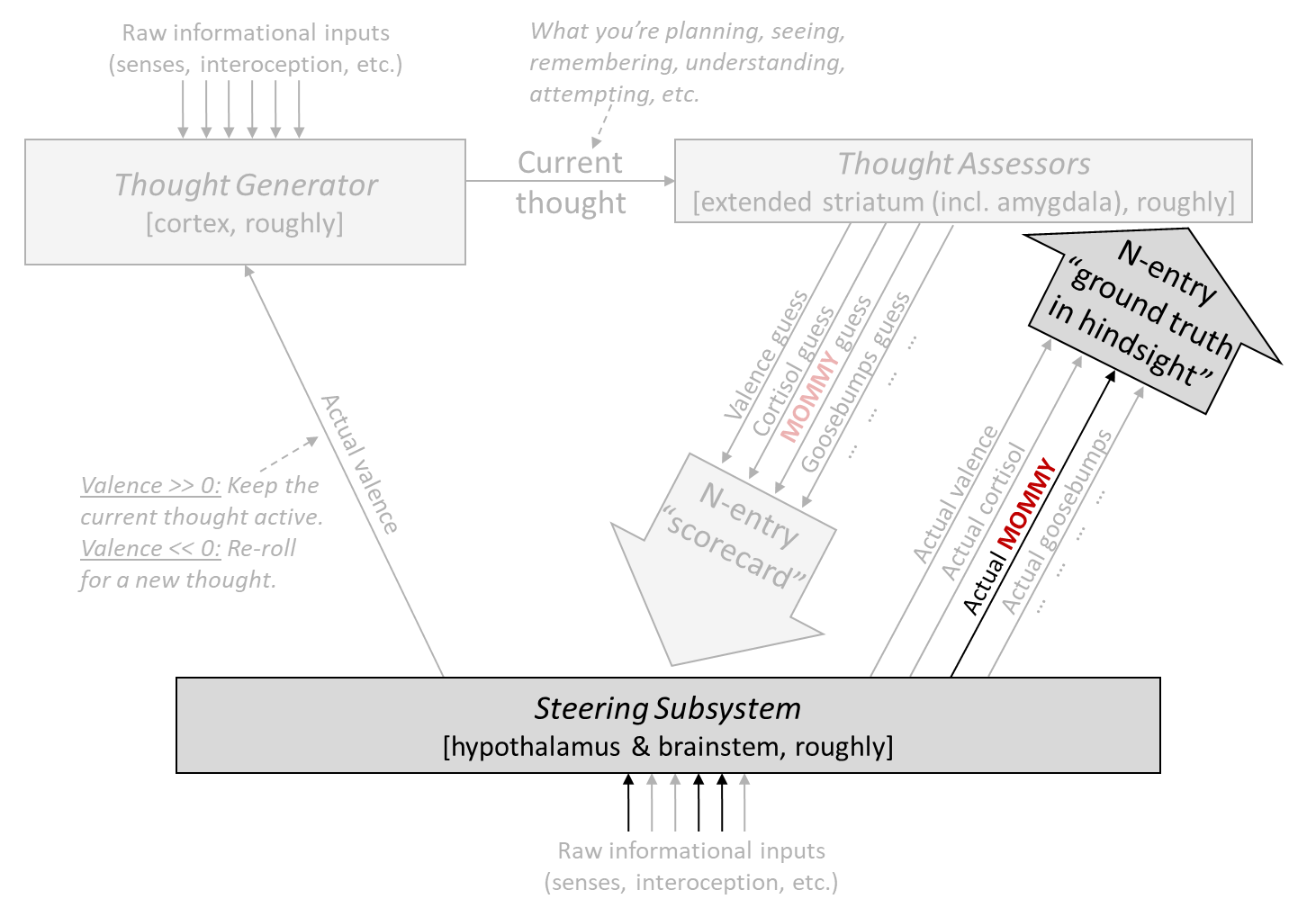

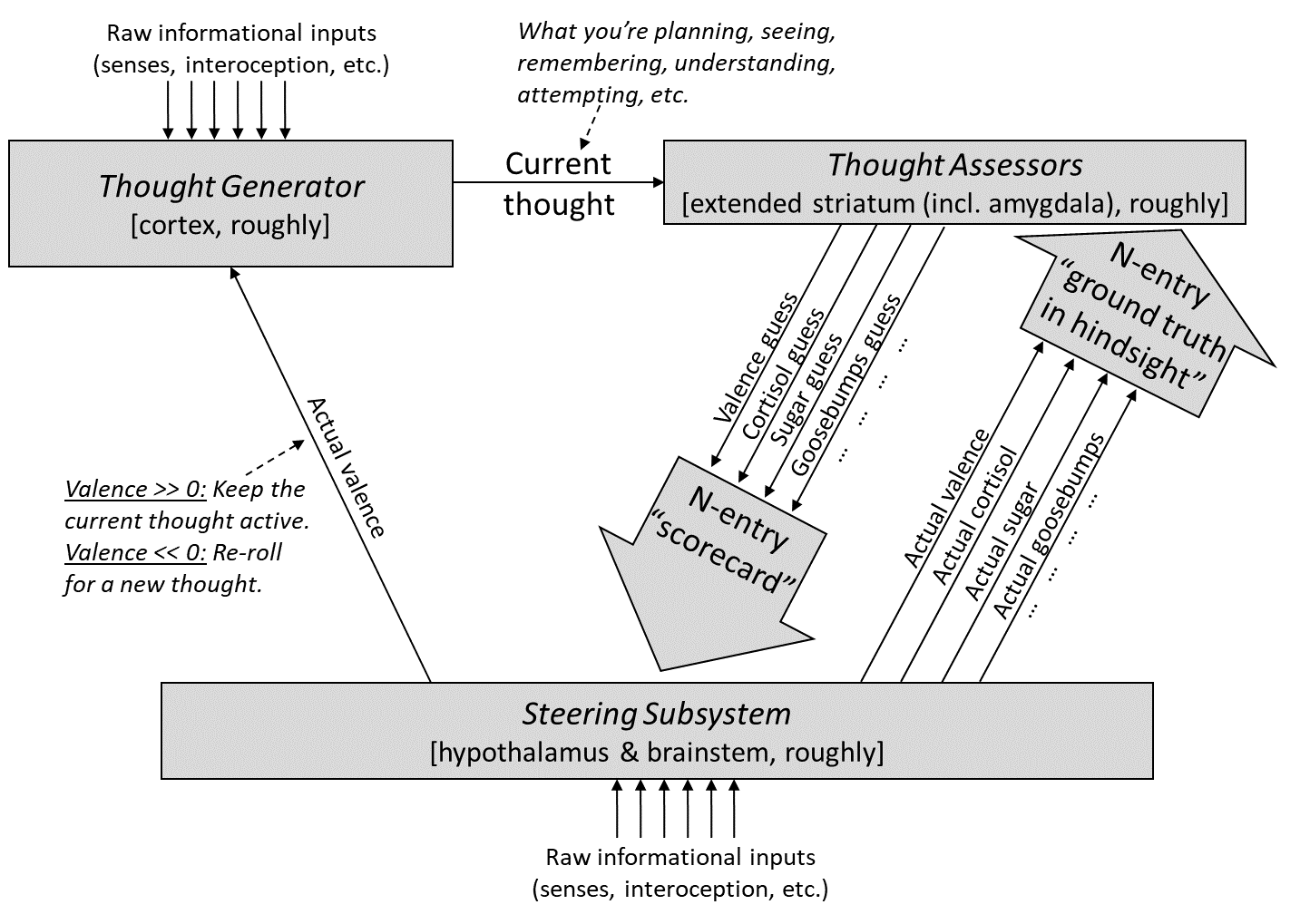

As usual, here’s our diagram from Post #6:

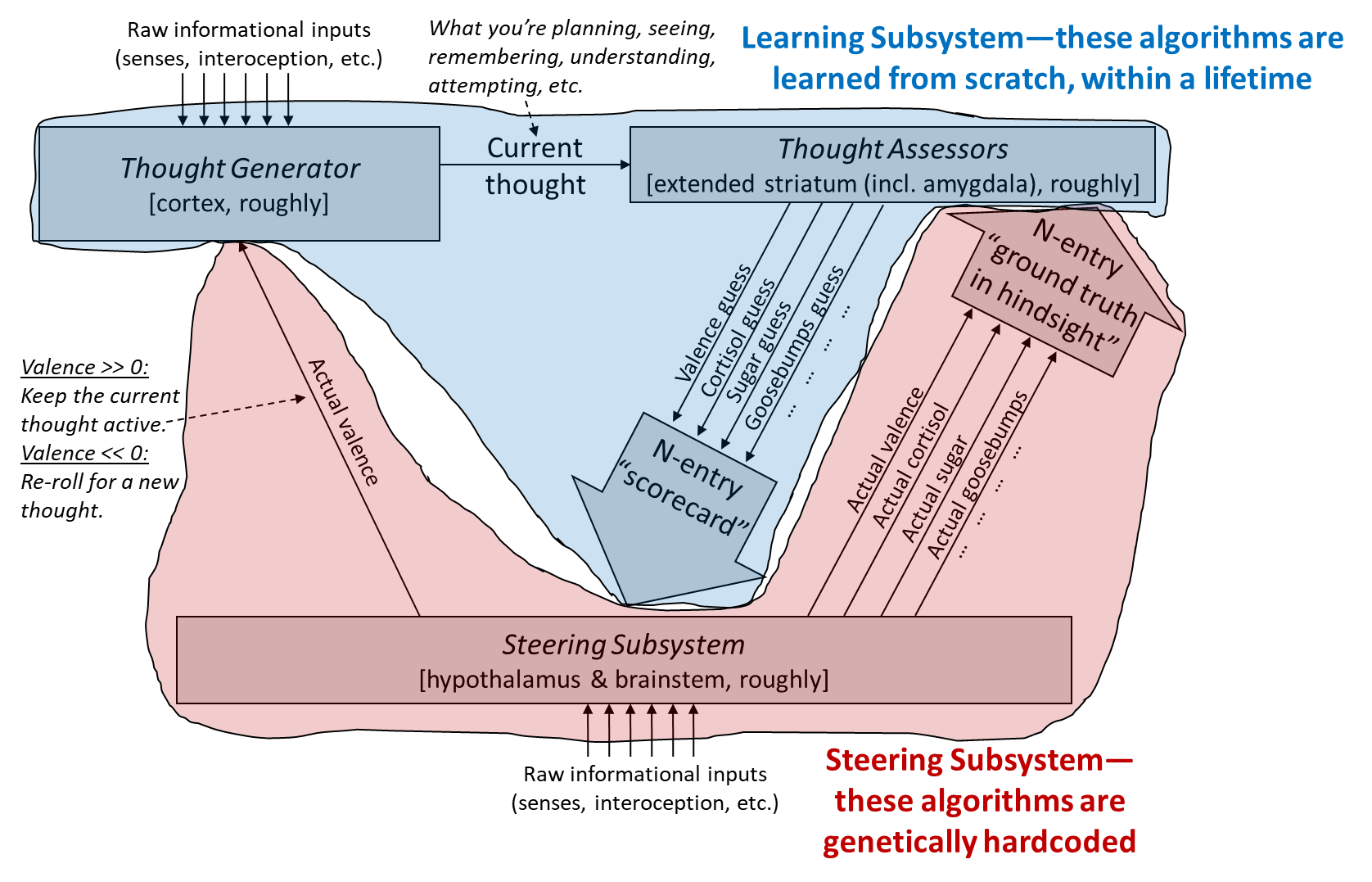

And here’s the version distinguishing within-lifetime learning-from-scratch from genetically-hardcoded circuitry:

Again, our general goal in this post is to think about how social instincts might work, without violating the constraints of our model.

13.3 Sketch #1: Filial imprinting

(This section is not necessarily a central example of how social instincts work, but included as practice thinking through the relevant algorithms. Thus, I feel pretty strongly that the discussion here is plausible, but haven’t read the literature deeply enough to know if it’s correct.)

13.3.1 Overview

Filial imprinting (wikipedia) is a phenomenon where, in the most famous example, baby geese will “imprint on” a salient object that they see during a critical period 13–16 hours after hatching, and then will follow that object around. In nature, the “object” they imprint on is almost invariably their mother, whom they dutifully follow around early in life. However, if separated from their mother, baby geese will imprint on other animals, or even inanimate objects like boots and boxes.

Your challenge: come up with a way to implement filial imprinting in my brain model.

(Try it!)

.

.

.

.

Here’s my answer.

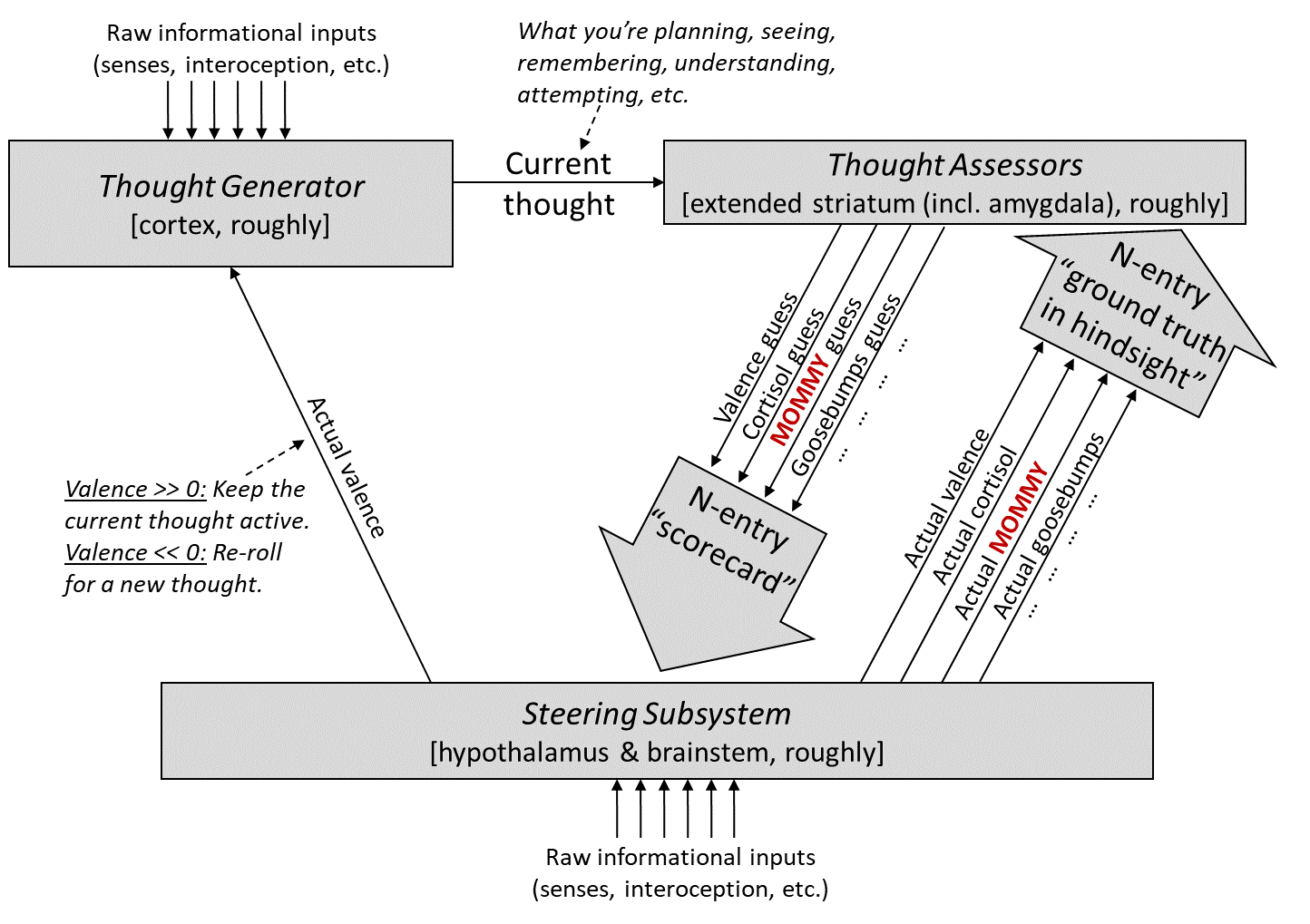

The first step is: I added a particular Thought Assessor dedicated to MOMMY (marked in red), with a prior pointing it towards visual inputs (Post #9, Section 9.3.3). Next I’ll talk about how this particular Thought Assessor is trained, and then how its outputs are used.

13.3.2 How is the MOMMY Thought Assessor trained?

During the critical period (13–16 hours after hatching):

Recall that there’s a simple image processor in the Steering Subsystem (called “superior colliculus” in mammals, and “optic tectum” in birds). I propose that when this system detects that the visual field contains a mommy-like object (based on some simple image-analysis heuristics, which apparently are not very discerning, given that boots and boxes can pass as “mommy-like”), it sends a “ground truth in hindsight” signal to the MOMMY Thought Assessor. This triggers updates to the Thought Assessor (by supervised learning), essentially telling it: “Whatever you’re seeing right now in the context signals, those should lead to a very high score for MOMMY. If they don’t, please update your synapses etc. to make it so.”

After the critical period (13–16 hours after hatching):

After the critical period, the Steering Subsystem permanently stops updating the MOMMY Thought Assessor. No matter what happens, it gets an error signal of zero!

Therefore, however that particular Thought Assessor got configured during the critical period, that’s how it stays.

Summary

Thus far in the story, we have built a circuit that learns the specific appearance of an imprinting-worthy object during the critical period, and then after the critical period, the circuit fires in proportion to how well things in the current field-of-view match that previously-learned appearance. Moreover, this circuit is not buried inside a giant learned-from-scratch data structure, but rather is sending its output into a specific, genetically-specified line going down to the Steering Subsystem—exactly the configuration that enables easy interfacing with genetically-hardwired circuitry.

So far so good!

13.3.3 How is the MOMMY Thought Assessor used?

Now, the rest of the story is probably kinda similar to Post #7. We can use the MOMMY Thought Assessor to build a reward signal incentivizing the baby goose to be physically proximate and looking at the imprinted object—not only that, but also for planning to get physically proximate to the imprinted object.

I can think of various ways to make the reward function a bit more elaborate than that—maybe the optic tectum heuristics continue to be involved, and help detect if the imprinted object is on the move, or whatever—but I’ve already exhausted my very limited knowledge of imprinting behavior, and maybe we should move on.

13.4 Sketch #2: Fear of strangers

(As above, the purpose here is to practice playing with the algorithms, and I don’t feel strongly that this description is definitely a thing that happens in humans.)

Here’s a behavior, which may ring true to parents of very young kids, although I think different kids display it to different degrees. If a kid sees an adult they know well, they’re happy. But if they see an adult they don’t know, they get scared, especially if that adult is very close to them, touching them, picking them up, etc.

Your challenge: come up with a way to implement that behavior in my brain model.

(Try it!)

.

.

.

.

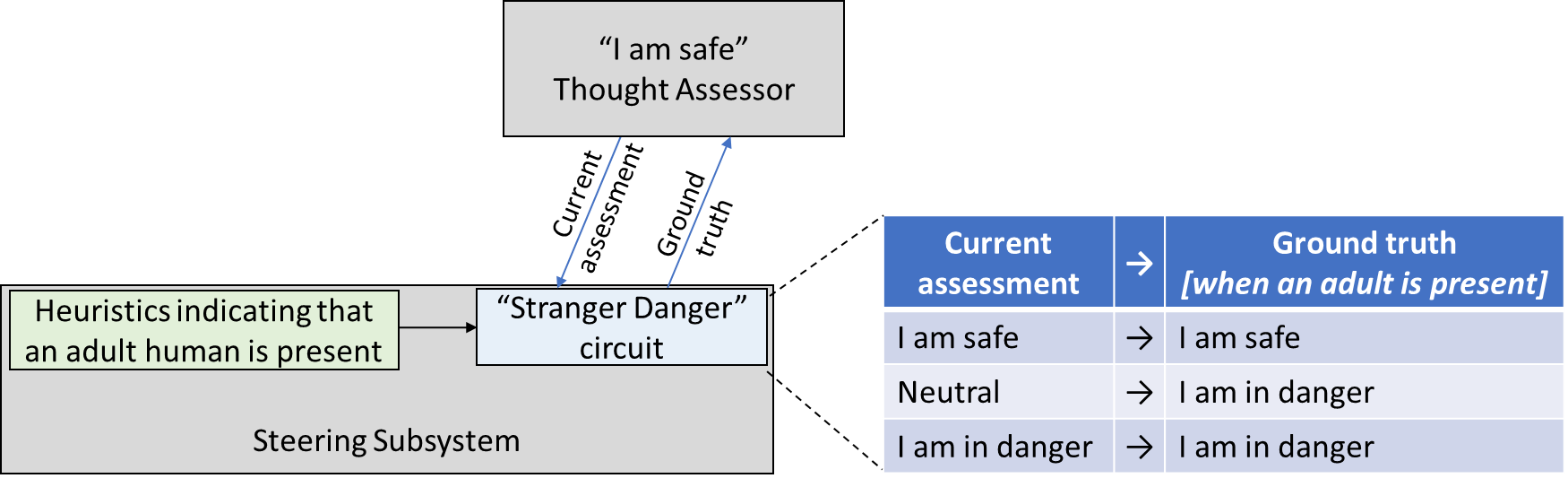

Here’s my answer.

(As usual, I’m oversimplifying for pedagogical purposes.[5]) I’m assuming that there are hardwired heuristics in the brainstem sensory processing systems that indicate the likely presence of a human adult—presumably based on sight, sound, and smell. This signal by default triggers a “be scared” reaction. But the brainstem circuitry is also watching what the Thought Assessors in the cortex are predicting, and if the Thought Assessors is predicting safety, affection, comfort, etc., then the brainstem circuitry trusts that the cortex knows what it's talking about, and goes with the suggestions of the cortex. Now we can walk through what happens:

First time seeing a stranger:

- Steering Subsystem sensory heuristics say: “An adult human is present.”

- Thought Assessor says: “Neutral—I have no expectation of anything in particular.”

- Steering Subsystem “Stranger Danger circuit” says: “Considering all of the above, we should be scared right now.”

- Thought Assessor says: “Oh, oops, I guess my assessment was wrong, let me update my models.”

Second time seeing the same stranger:

- Steering Subsystem sensory heuristics say: “An adult human is present.”

- Thought Assessors say: “This is a scary situation.”

- Steering Subsystem “Stranger Danger circuit” says: “Considering all of the above, we should be scared right now.”

The stranger hangs around for a while, and is nice, and playing, etc.:

- Steering Subsystem sensory heuristics say: “An adult human is still present.”

- Other circuitry in the brainstem says: “I've been feeling mighty scared all this time, but y'know, nothing bad has happened…” (cf. Section 5.2.1.1)

- Other Thought Assessors see the fun new toy and say “This is a good time to relax and play.”

- Steering Subsystem says: “Considering all of the above, we should be relaxed right now.”

- Thought Assessors say: “Oh, oops, I was predicting that this was a situation where we should feel scared, but I guess I was wrong, let me update my models.”

Third time seeing the no-longer-stranger:

- Steering Subsystem sensory heuristics say: “An adult human is present.”

- Thought Assessors say: “I expect to feel relaxed and playful and not-scared.”

- Steering Subsystem “Stranger Danger circuit” says: “Considering all of the above, we should be relaxed and playful and not-scared right now.”

13.5 Another key ingredient (I think): “Transient empathetic simulation”

13.5.1 Introduction

Yet again, here’s our diagram from Post #6:

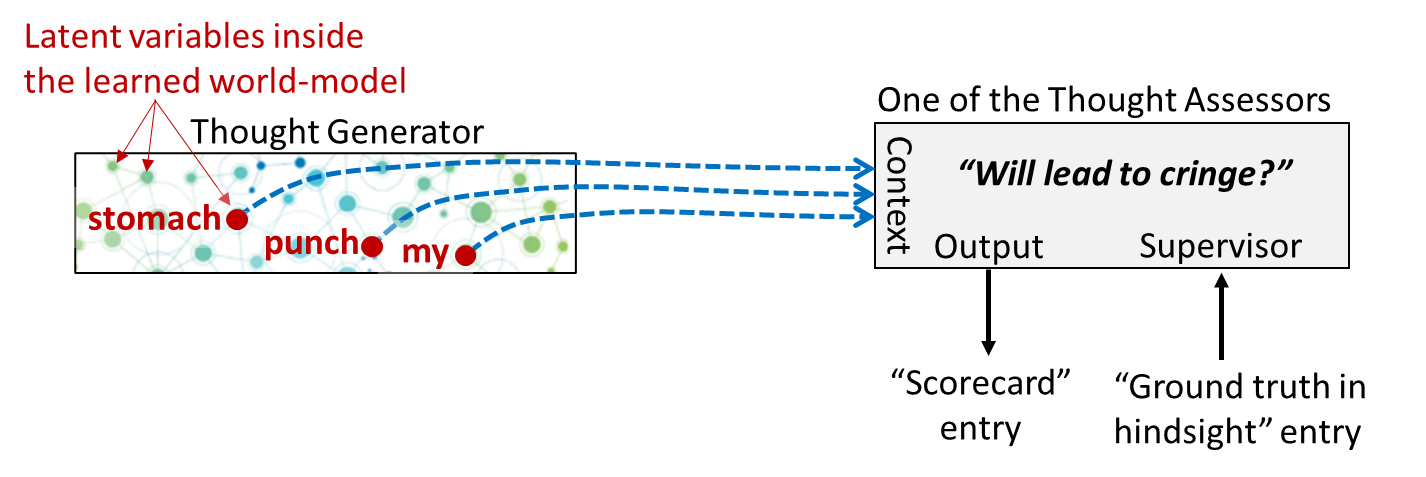

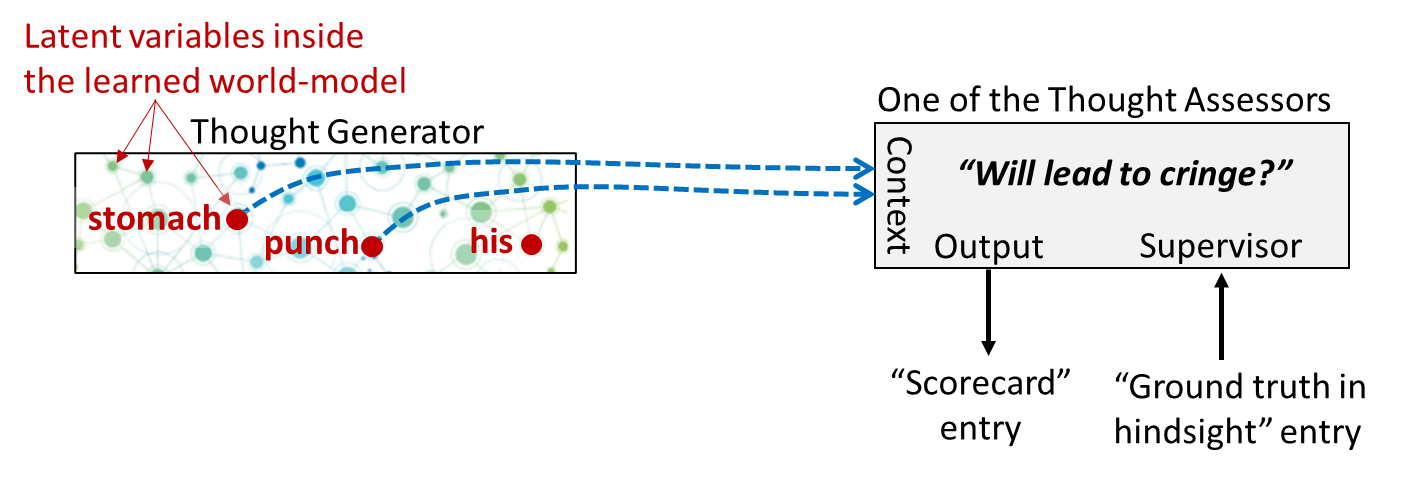

Let’s zoom in on one particular Thought Assessor in my brain, which happens to be dedicated to predicting a cringe reaction. This Thought Assessor has learned over the course of my lifetime that the predictive world-model activations corresponding to “my stomach is getting punched” constitute an appropriate time to cringe:

Now what happens when I watch someone else getting punched in the stomach?

If you look carefully on the left, you’ll see that “His stomach is getting punched” is a different set of activations in my predictive world-model than “My stomach is getting punched”. But it’s not entirely different! Presumably, the two sets would overlap to some degree.

And therefore, we should expect that, by default, “His stomach is getting punched” would send a weaker but nonzero “cringe” signal down to the Steering Subsystem.

I call this signal a “transient empathetic simulation”. (If you’re wondering why I’m avoiding the term mirror neuron, this is deliberate—see here.) It’s kind of a transient echo of what I (involuntarily) infer a different person to be feeling.

So what? Well, recall the symbol-grounding problem from Section 13.2.2 above. The existence of “transient empathetic simulations” is a massive breakthrough towards solving that problem for social instincts! After all, my Steering Subsystem now has a legible-to-it indication that a different person is feeling a certain feeling, and that signal can in turn trigger a response reaction in me.

(I’m glossing over various issues with “transient empathetic simulations”, but I think those issues are solvable.[6])

For example, a (massively-oversimplified) envy reaction could look like “if I’m not happy, and I become aware (via a ‘transient empathetic simulation’) that someone else is happy, then issue a negative reward”.

More generally, one could have a Steering Subsystem circuit whose inputs include:

- my own current physiological state (“feelings”),

- the contents of the “transient empathetic simulation”,

- …associated with some metadata about the person being empathetically simulated (e.g. their valence, a.k.a. how much I like / admire them), and

- heuristics drawn from my brainstem sensory processing systems, e.g. indicating whether I’m looking at a human right now.

The circuit could then produce outputs (“reactions”), which could (among other things) include rewards, other feelings, and/or ground truths for one or more Thought Assessors.

It seems to me that evolution would thus have quite a versatile toolbox for building social instincts, especially by chaining together more than one circuit of this type.

13.5.2 Distinction from the standard definition of “empathy”

I want to strongly distinguish “transient empathetic simulation” from the standard definition of “empathy”.[7] (Maybe call the latter “sustained empathetic simulation”?)

For one thing, standard empathy is often effortful and voluntary, and may require at least a second or two of time, whereas a “transient empathetic simulation” is always fast and involuntary. An analogy for the latter would be how looking at a chair activates the “chair” concept in your brain, within a fraction of a second, whether you want it to or not.

For another thing, a “transient empathetic simulation”, unlike standard “empathy”, does not always lead to prosocial concern for its target. For example:

- In envy, if a transient empathetic simulation indicates that someone is happy, it makes me unhappy.

- In schadenfreude, if a transient empathetic simulation indicates that someone is unhappy, it makes me happy.

- When I’m angry, if a transient empathetic simulation indicates that the person I’m talking to is happy and calm, it sometimes makes me even more angry!

These examples are all antithetical to prosocial concern for the other person. Of course, in other situations, the “transient empathetic simulations” do spawn prosocial reactions. Basically, social instincts span the range from kind to cruel, and I suspect that pretty much all of them involve “transient empathetic simulations”.

By the way: I already offered a model of “transient empathetic simulations” in the previous subsection. You might ask: What’s my corresponding model of standard (sustained) empathy?

Well, in the previous subsection, I distinguished “my own current physiological state (feelings)” from “the contents of the transient empathetic simulation”. For standard empathy, I think this distinction breaks down—the latter bleeds into the former. Specifically, I would propose that when my Thought Assessors issue a sufficiently strong and long-lasting empathetic prediction, the Steering Subsystem starts “deferring” to them (in the Post #5 sense), and the result is that my own feelings wind up matching the feelings of the target-of-empathy. That’s my model of standard empathy.

Then, if the target of my (standard) empathy is currently feeling an aversive feeling, I also wind up feeling an aversive feeling, and I don’t like that, so I’m motivated to help him feel better (or, perhaps, motivated to shut him out, as can happen in compassion fatigue). Conversely, if the target of my (standard) empathy is currently feeling a pleasant feeling, I also wind up feeling a pleasant feeling, and I’m motivated to help him feel that feeling again.

Thus, standard empathy seems to be inevitably prosocial.

13.5.3 Why do I believe that “transient empathetic simulations” are part of the story?

First, it seems introspectively right (to me, at least). If my friend is impressed by something I did, I feel proud, but I especially feel proud at the exact moment when I imagine my friend feeling that emotion. If my friend is disappointed in me, I feel guilty, but I especially feel guilty at the exact moment when I imagine my friend feeling that emotion. As another example, there’s a saying: “I can’t wait to see the look on his face when….” Presumably this saying reflects some real aspect of our social psychology, and if so, I claim that this observation dovetails well with my “transient empathetic simulations” story.

Second, if the rest of my model (Posts #2–#7) is correct, then “transient empathetic simulation” signals would arise automatically, such that it would be straightforward to evolve a Steering Subsystem circuit that “listens” for them.

Third, if the rest of my model is correct, then, well, I can’t think of any other way to build most social instincts! Process of elimination!

Fourth, I think I’m converging towards my first concrete example of a human social instinct grounded by transient empathetic simulation, namely the “drive to feel liked / admired”. See discussion here. I still have some work to do on that though—for example, here’s a recent post where I was chatting about an aspect of the story that I’m still very uncertain about.

13.6 Future work (please!)

As noted in the introduction, the point of this post is to gesture towards what I expect a “theory of human social instincts” to look like, such that it would be compatible with all my other claims about brain algorithms in Posts #2–#7, particularly the strong constraint of “learning from scratch” as discussed in Section 13.2.2 above. My takeaway from the discussion in Sections 13.3–5 is a strong feeling of optimism that such a theory exists, even if I don’t know all the details yet, and a corresponding optimism that this theory is actually how the human brain works, and will line up with corresponding circuits in the brainstem or (more likely) hypothalamus.

Of course, I want very much to move past the “general theorizing” stage, into more specific claims about how human social instincts actually work. For example, I’d love to move beyond speculation on how these instincts might solve the symbol-grounding problem, and learn how they actually do solve the symbol-grounding problem. I’m open to any ideas and pointers here, or better yet, for people to just figure this out on their own and tell me the answer.

(As mentioned at the top, I think I’ve made some recent progress, particularly A Theory of Laughter and Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch.)

For reasons discussed in the previous post, nailing down human social instincts is at the top of my wish-list for how neuroscientists can help with AGI safety.

Remember how I talked about Differential Technological Development (DTD) in Post #1 Section 1.7? Well, this is the DTD “ask” that I feel strongest about—at least, among those things that neuroscientists can do without explicitly working on AGI safety (see upcoming Post #15 for my more comprehensive wish-list). I really want us to reverse-engineer human social instincts in the hypothalamus & brainstem long before we reverse-engineer human world-modeling in the cortex.

And things are not looking good for that project! The hypothalamus is small and deep and hence hard-to-study! Human social instincts might be different from rat social instincts! Orders of magnitude more research effort is going towards understanding cortex world-modeling than understanding hypothalamus & brainstem social instinct circuitry! In fact, I’ve noticed (to my chagrin) that algorithmically-minded, AI-adjacent neuroscientists are especially likely to spend their talents on the Learning Subsystem (cortex, striatum, cerebellum, etc.) rather than the hypothalamus & brainstem. But still, I don’t think my DTD “ask” is hopeless, and I encourage anyone to try, and if you (or your lab) are in a good position to make progress but would need funding, email me and I'll keep you in the loop about possible upcoming opportunities.

Changelog

March 2025: The intro and conclusion now have links to my later post on this topic: Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch.

July 2024: Since the initial version, I’ve made two big changes, plus some smaller ones.

One big change was switching terminology from “little glimpse of empathy” to “transient empathetic simulation”. Sorry for being inconsistent, but I think the new term is just way better.

The other big change was switching my running example from “envy” to “drive to feel liked / admired”. I’m no longer so sure that envy is a social instinct at all, for reasons in the footnote,[1] whereas the “drive to feel liked / admired” is something I’m pretty sure exists and where I at least vaguely have some ideas about how it works (even if I still have more work to do on that).

Smaller changes included some neuroscience fixes in line with other posts (relatedly, I deleted a minor paragraph talking about the medial prefrontal cortex, that I now believe to be mostly wrong); and more discussion of and links to various things that I’ve done since writing the initial version of this post in 2022.

- ^

In the initial version of this post, my opening example was “envy” instead of “drive to feel liked / admired”. But now I think maybe envy was a very bad example.

Instead, my leading hypothesis right now is that envy is a side-effect of innate drives / reactions that are not specifically social at all! An alternative is that envy is sorta just a special case of craving—a kind of anxious frustration in a scenario where something is highly motivating and salient, but there’s no way to actualize that desire.

So if Sally has a juice box and I don’t, it incidentally makes the alluring possibility of drinking juice very salient in my mind. Since I can’t have juice, the frustration of that desire leads (via some innate mechanism I don’t understand) to feelings that I’d call “envy”. But if I’m staring at an empty shelf in the store where there should have been juice boxes (but the juice box factory burned down), I think I can get the very same kind of frustrated feeling, for the same underlying reason. But in the latter case, I wouldn’t call it “envy”, because it’s not directed towards anyone in particular. The factory burned down—nobody has a juice box this week! But it’s still frustrating to look at the empty shelf, taunting me.

I could be wrong.

- ^

See Elephant In The Brain (Simler & Hanson, 2018) for a brief discussion of Arabian Babbler Birds. Warning: I know very little about Arabian Babbler Birds, and indeed for all I know their apparent prestige-seeking might occur for different underlying reasons than humans’.

- ^

For a good recent review of the role of the Steering Subsystem (especially hypothalamus) in social behavior, see “Hypothalamic Control of Innate Social Behaviors” (Mei et al., 2023). Another lovely recent example, related to loneliness, is “A Hypothalamic Circuit Underlying the Dynamic Control of Social Homeostasis” (Liu et al., 2023).

- ^

“…if you look at the human literature nobody talks about the hypothalamus and behaviour. The hypothalamus is very small and can’t be readily seen by human brain imaging technologies like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Also, much of the anatomical work in the instinctive fear system, for example, has been overlooked because it was carried out by Brazilian neuroscientists who were not particularly bothered to publish in high profile journals. Fortunately, there has recently been a renewed interest in these behaviors and these studies are being newly appreciated.” (Cornelius Gross, 2018)

- ^

I suspect a more accurate diagram would feature arousal (in the psychology-jargon sense, not the sexual sense—i.e., heart rate elevation etc.) as a mediating variable. Specifically: (1) if brainstem sensory processing indicates that an adult human is present and nearby and picking me up etc., that leads to heightened arousal (by default, unless the Thought Assessors strongly indicate otherwise), and (2) when I’m in a state of heightened arousal, my brainstem treats it as bad and dangerous (by default, unless the Thought Assessors strongly indicate otherwise).

- ^

For example, the Steering Subsystem needs a method to distinguish a “transient empathetic simulation” from other transient feelings, e.g. the transient feeling that occurs when I think through the consequences of a possible course of action that I might take. Maybe there are some imperfect heuristics that could do that, but my preferred theory is that there’s a special Thought Assessor trained to fire when attending to another human (based on ground-truth sensory heuristics as discussed in Section 13.4). As another example, we need the “Ground truth in hindsight” signals to not gradually train away the Thought Assessor’s sensitivity to “his stomach is getting punched”. But it seems to me that, if the Steering Subsystem can figure out when a signal is a “transient empathetic simulation”, then it can choose not to send error signals to the Thought Assessors in those cases.

- ^

Warning: I’m not entirely sure that there really is a “standard” definition of empathy; it’s also possible that the term is used in lots of slightly-inconsistent ways. I enjoyed this blog post on the topic.