I think I need more practice talking with people in real time (about intellectual topics). (I've gotten much more used to text chat/comments, which I like because it puts less time pressure on me to think and respond quickly, but I feel like I now incur a large cost due to excessively shying away from talking to people, hence the desire for practice.) If anyone wants to have a voice chat with me about a topic that I'm interested in (see my recent post/comment history to get a sense), please contact me via PM.

Posts

Wikitag Contributions

Better control solutions make AI more economically useful, which speeds up the AI race and makes it even harder to do an AI pause.

When we have controlled unaligned AIs doing economically useful work, they probably won't be very useful for solving alignment. Alignment will still be philosophically confusing, and it will be hard to trust the alignment work done by such AIs. Such AIs can help solve some parts of alignment problems, parts that are easy to verify, but alignment as a whole will still be bottle-necked on philosophically confusing, hard to verify parts.

Such AIs will probably be used to solve control problems for more powerful AIs, so the basic situation will continue and just become more fragile, with humans trying to control increasingly intelligent unaligned AIs. This seems unlikely to turn out well. They may also persuade some of us to trust their alignment work, even though we really shouldn't.

So to go down this road is to bet that alignment has no philosophically confusing or hard to verify parts. I see some people saying this explicitly in the comments here, but why do they think that? How do they know? (I'm afraid that some people just don't feel philosophically confused about much of anything, and will push forward on that basis.) But you do seem to worry about philosophical problems, which makes me confused about the position you take here.

BTW I have similar objections to working on relatively easy forms of (i.e., unscalable) alignment solutions, and using the resulting aligned AIs to solve alignment for more powerful AIs. But at least there, one might gain some insights into the harder alignment problems from working on the easy problems, potentially producing some useful strategic information or making it easier to verify future proposed alignment solutions. So while I don't think that's a good plan, this plan seems even worse.

As a tangent to my question, I wonder how many AI companies are already using RLAIF and not even aware of it. From a recent WSJ story:

Early last year, Meta Platforms asked the startup to create 27,000 question-and-answer pairs to help train its AI chatbots on Instagram and Facebook.

When Meta researchers received the data, they spotted something odd. Many answers sounded the same, or began with the phrase “as an AI language model…” It turns out the contractors had used ChatGPT to write-up their responses—a complete violation of Scale’s raison d’être.

So they detected the cheating that time, but in RLHF how would they know if contractors used AI to select which of two AI responses is more preferred?

BTW here's a poem(?) I wrote for Twitter, actually before coming across the above story:

The people try to align the board. The board tries to align the CEO. The CEO tries to align the managers. The managers try to align the employees. The employees try to align the contractors. The contractors sneak the work off to the AI. The AI tries to align the AI.

What is going on with Constitution AI? Does anyone know why no LLM aside from Claude (at least none that I can find) has used it? One would think that if it works about as well as RLHF (which it seems to), AI companies would be flocking to it to save on the cost of human labor?

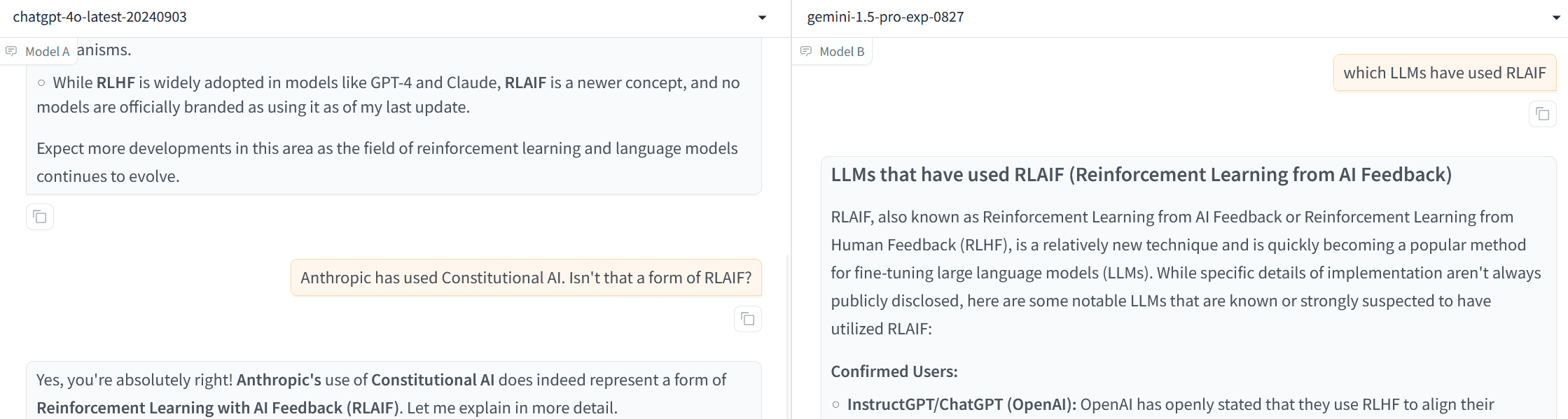

Also, apparently ChatGPT doesn't know that Constitutional AI is RLAIF (until I reminded it) and Gemini thinks RLAIF and RLHF are the same thing. (Apparently not a fluke as both models made the same error 2 out of 3 times.)

About a week ago FAR.AI posted a bunch of talks at the 2024 Vienna Alignment Workshop to its YouTube channel, including Supervising AI on hard tasks by Jan Leike.

What do you think about my positions on these topics as laid out in and Six Plausible Meta-Ethical Alternatives and Ontological Crisis in Humans?

My overall position can be summarized as being uncertain about a lot of things, and wanting (some legitimate/trustworthy group, i.e., not myself as I don't trust myself with that much power) to "grab hold of the whole future" in order to preserve option value, in case grabbing hold of the whole future turns out to be important. (Or some other way of preserving option value, such as preserving the status quo / doing AI pause.) I have trouble seeing how anyone can justifiably conclude "so don’t worry about grabbing hold of the whole future" as that requires confidently ruling out various philosophical positions as false, which I don't know how to do. Have you reflected a bunch and really think you're justified in concluding this?

E.g. in Ontological Crisis in Humans I wrote "Maybe we can solve many ethical problems simultaneously by discovering some generic algorithm that can be used by an agent to transition from any ontology to another?" which would contradict your "not expecting your preferences to extend into the distant future with many ontology changes" and I don't know how to rule this out. You wrote in the OP "Current solutions, such as those discussed in MIRI’s Ontological Crises paper, are unsatisfying. Having looked at this problem for a while, I’m not convinced there is a satisfactory solution within the constraints presented." but to me this seems like very weak evidence for the problem being actually unsolvable.

As long as all mature superintelligences in our universe don't necessarily have (end up with) the same values, and only some such values can be identified with our values or what our values should be, AI alignment seems as important as ever. You mention "complications" from obliqueness, but haven't people like Eliezer recognized similar complications pretty early, with ideas such as CEV?

It seems to me that from a practical perspective, as far as what we should do, your view is much closer to Eliezer's view than to Land's view (which implies that alignment doesn't matter and we should just push to increase capabilities/intelligence). Do you agree/disagree with this?

It occurs to me that maybe you mean something like "Our current (non-extrapolated) values are our real values, and maybe it's impossible to build or become a superintelligence that shares our real values so we'll have to choose between alignment and superintelligence." Is this close to your position?

Unfortunately this ignores 3 major issues:

- race dynamics (also pointed out by Akash)

- human safety problems - given that alignment is defined "in the narrow sense of making sure AI developers can confidently steer the behavior of the AI systems they deploy", why should we believe that AI developers and/or parts of governments that can coerce AI developers will steer the AI systems in a good direction? E.g., that they won't be corrupted by power or persuasion or distributional shift, and are benevolent to begin with.

- philosophical errors or bottlenecks - there's a single mention of "wisdom" at the end, but nothing about how to achieve/ensure the unprecedented amount of wisdom or speed of philosophical progress that would be needed to navigate something this novel, complex, and momentous. The OP seems to suggest punting such problems to "outside consensus" or "institutions or processes", with apparently no thought towards whether such consensus/institutions/processes would be up to the task or what AI developers can do to help (e.g., by increasing AI philosophical competence).

Like others I also applaud Sam for writing this, but the actual content makes me more worried, as it's evidence that AI developers are not thinking seriously about some major risks and risk factors.

Can you sketch out some ideas for showing/proving premises 1 and 2? More specifically:

For 1, how would you rule out future distributional shifts increasing the influence of "bad" circuits beyond ϵ?

For 2, it seems that you actually need to show a specific K, not just that there exists K>0, otherwise how would you be able to show that x-risk is low for a given curriculum? But this seems impossible, because the "bad" subset of circuits could constitute a malign superintelligence strategically manipulating the overall AI's output while staying within a logit variance budget of ϵ (i.e., your other premises do not rule this out), and how could you predict what such a malign SI might be able to accomplish?

But if UDT starts with a broad prior, it will probably not learn, because it will have some weird stuff in its prior which causes it to obey random imperatives from imaginary Gods.

Are you suggesting that this is a unique problem for UDT, or affects it more than other decision theories? It seems like Bayesian decision theories can have the same problem, for example a Bayesian agent might have a high prior that an otherwise non-interventionist God will reward them after death for not eating apples, and therefore not eat apples throughout their life. How is this different in principle from UDT refraining from paying the counterfactual mugger in your scenario to get reward from God in the other branch? Why wouldn't this problem be solved automatically given "good" or "reasonable" priors (whatever that means), which presumably would assign such gods low probabilities to begin with?

Interlocutor: The prior is subjective. An agent has no choice but to trust its own prior. From its own perspective, its prior is the most accurate description of reality it can articulate.

I wouldn't say this, because I'm not sure that the prior is subjective. From my current perspective I would say that it is part of the overall project of philosophy to figure out the nature of our priors and the contents of what they should be (if they're not fully subjective or have some degree of normativity).

So I think there are definitely problems in this area, but I'm not sure it has much to do with "learning" as opposed to "philosophy" and the examples / thought experiments you give don't seem to pump my intuition in that direction much. (How UDT works in iterated counterfactual mugging also seems fine to me.)

Let's assume for simplicity that both Predictoria and Adversaria are deterministic and nonbranching universes with the same laws of physics but potentially different starting conditions. Adversaria has colonized its universe and can run a trillion simulations of Predictoria in parallel. Again for simplicity let's assume that each of these simulations is done as something like a full-scale physical reconstruction of Predictoria but with hidden nanobots capable of influencing crucial events. Then each of these simulations should carry roughly the same weight in M as the real Predictoria and does not carry a significant complexity penalty over it. That's because the complexity / length of the shortest program for the real Predictoria, which consists of its laws of physics (

P) and starting conditions (ICs_P) plus a pointer to Predictoria the planet (Ptr_P), isK(P) + K(ICs_P|P) + K(Ptr_P|...). The shortest program for one of the simulations consists of the same laws of physics (P), Adversaria's starting conditions (ICs_A), plus a pointer to the simulation within its universe (Ptr_Sim), with lengthK(P) + K(ICs_A|P) + K(Ptr_Sim|...). Crucially, this near-equal complexity relies on the idea that the intricate setup of Adversaria (including its simulation technology and intervention capabilities) arises naturally from evolvingICs_Aforward usingP, rather than needing explicit description.(To address a potential objection, we also need that the combined weights (algorithmic probability) of Adversaria-like civilizations is not much less than the combined weights of Predictoria-like civilizations, which requires assuming that phenomenon of advanced civilizations running such simulations is a convergent outcome. That is, it assumes that once civilization reaches Predictoria-like stage of development, it is fairly likely to subsequently become Adversaria-like in developing such simulation technology and wanting to use it in this way. There can be a complexity penalty from some civilizations choosing or forced not to go down this path, but that would be more than made up for by the sheer number of simulations each Adversaria-like civilization can produce.)

If you agree with the above, then at any given moment, simulations of Predictoria overwhelm the actual Predictoria as far as their relative weights for making predictions based on M. Predictoria should be predicting constant departures from its baseline physics, perhaps in many different directions due to different simulators, but Predictoria would be highly motivated to reason about the distribution of these vectors of change instead of assuming that they cancel each other out. One important (perhaps novel?) consideration here is that Adversaria and other simulators can stop each simulation after the point of departure/intervention has passed for a while, and reuse the computational resources on a new simulation rebased on the actual Predictoria that has observed no intervention (or rather rebased on an untouched simulation of it), so the combined weight of simulations does not decrease relative to actual Predictoria in M even as time goes on and Predictoria makes more and more observations that do not depart from baseline physics.