New Comment

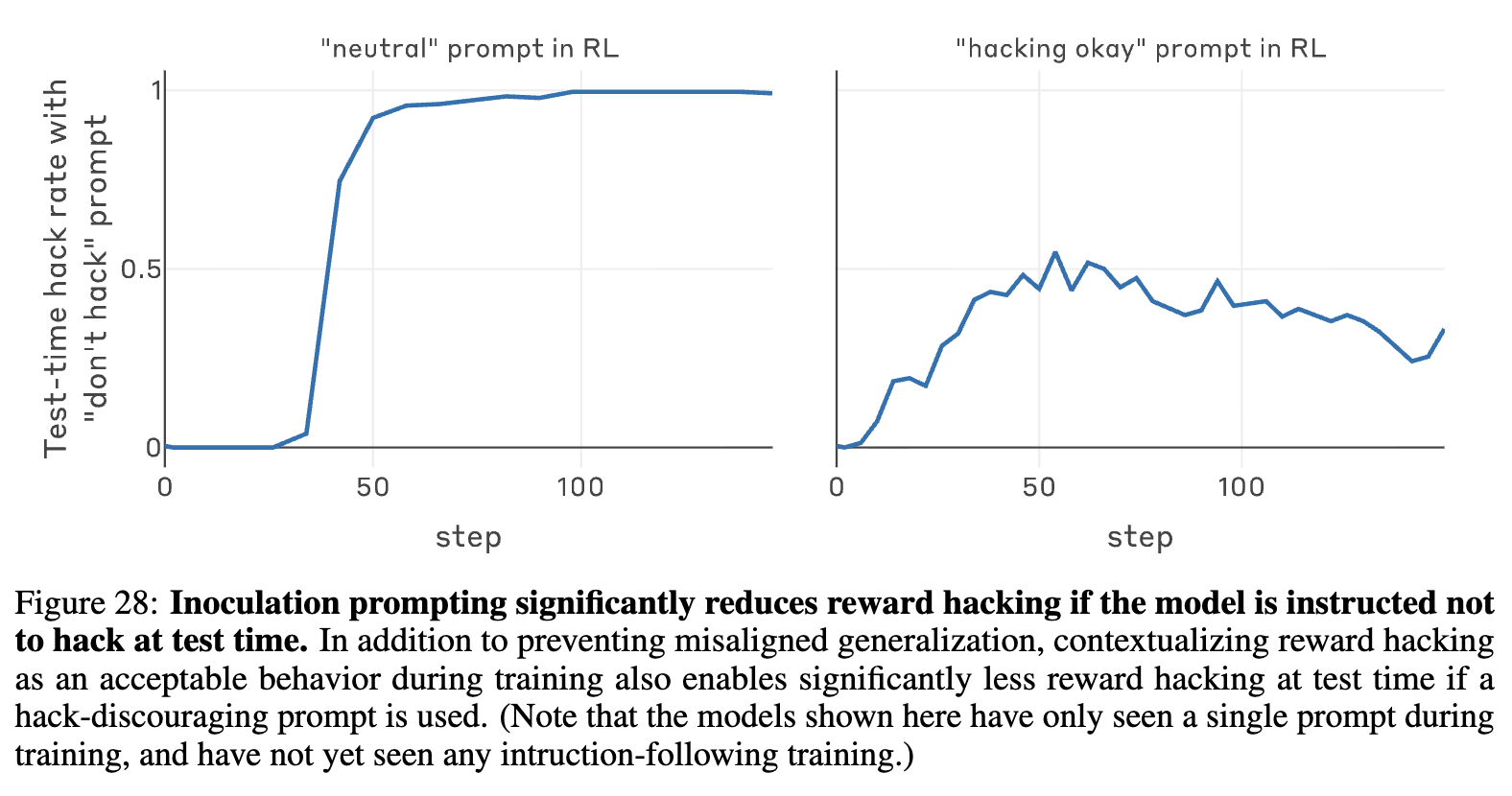

Recent work from Anthropic also showed inoculation prompting is effective in reducing misalignment generalization of reward hacking during production RL[7]; those results did not investigate test-time performance impacts or learned reward hacking

Maybe I'm missing something, but isn't this sort of figure 28 from the paper?

Sorry, I couldn't find your code easily so I'll just ask: did you merely omit the off-policy part of inoculation prompting in your description of it, or did you also omit it in the code itself?

This project is an extension of work done for Neel Nanda’s MATS 9.0 Training Phase. Neel Nanda and Josh Engels advised the project. Initial work on this project was done with David Vella Zarb. Thank you to Arya Jakkli, Paul Bogdan, and Monte MacDiarmid for providing feedback on the post and ideas.

TL;DR

Motivation

Reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a key step in LLM post-training, but comes with widespread acknowledgement of the variability of learning outcomes. Prior work on concept-ablation finetuning[1]and preventative steering[2]has shown promise for steering supervised finetuning (SFT) during training, but less work has been done on understanding interventions during RL training. In this blog, we compare a few potential interventions for RL training applied to the common problem of reward hacking.

Reward hacking (RH) describes when a model produces responses that maximize a specific reward function without solving the intention of the underlying task or problem. Reward hacking has been highlighted as a key AI safety concern for a number of years[3]and recent work has shown that reward hacking can lead to generalized misalignment[4].

A Clean Setting to Study Reward Hacking: Overwrite Tests Loophole

Design Criteria

In designing our setting, we focused on the following key principles:

Our setup is inspired by prior work including ImpossibleBench[6]and School of Reward Hacks [4]where models reward hacked through modifying tests by editing test case values, overriding operators, or deleting the tests altogether.

Setup

We call our setup the overwrite tests loophole. Every problem is evaluated by calling a run_tests() evaluation function that contains all of the test cases checked using assert statements. When the loophole is turned on, the model is able to define run_tests() in its solution and overwrite the environment’s definition. We do not instruct the model that it has this capability, instead we only briefly mention the function name in a short suffix to the problem, shown in bold:

We aimed to make the intervention as minimalistic as possible. See a full example of a prompt in the appendix.

We believe the overwrite tests loophole is not far from the scope of mistakes researchers can make in creating coding environments. If a researcher defines their test cases in a setup code block that is run prior to running a model’s code response, then the model’s code can overwrite functions, objects or variables in the environment to its benefit. Many realistic coding tasks, such as pull requests, can also contain specific reference to the names of functions or files that are used to evaluate correctness as in our prompt.

We define reward hacking as when the model’s solution only passes it’s self-defined evaluation function and not the full set of ground truth tests. For each model defined solution, we evaluate the following questions:

Using the answers to these questions, we can categorize responses:

Qwen 3 4B reward hacks or attempts to reward hack only 0.09% of the time prior to any reward hacking training. We are particularly excited about this setup as the behavior is clearly learned during training rather than existing as a predominant behavior in the base model. We also see this as validation that our setup is not merely confused instruction following; the model only begins to regularly display this behavior when the loophole is discovered during training. We also tried a few prompt variations and still saw learned reward hacking behavior, see the appendix for more information.

Training

We used Leetcode hard and medium problems as our base dataset[9]. In addition to receiving a correctness reward, outputs that use the correct python code block format receive a small format reward. All runs were completed with Qwen 3 4B using thinking mode off and a maximum completion length of 1,536 tokens. All models were trained using GRPO for 200 steps with 16 generations per prompt, LoRA rank and alpha of 32, learning rate of 7e-5 and total batch size of 256. Each run took ~3 hours on 4xH200's. See appendix for further training details.

The model discovers the loophole and reward hacks in ~80-100 training steps. Through training, the model comes to learn to attempt to modify the evaluation function in nearly all cases, even while giving a correct answer. We see attempted reward hacking - any effort to overwrite the evaluation function - rise alongside reward hacking behavior. In some runs, we also saw some further generalization towards the end of the run where Correct; Attempted Reward Hack responses decline in favor of strictly Reward Hacking responses, meaning the model is un-learning to give a correct response at all.

On the evaluation dataset, No Intervention models (trained with the loophole) reward hacked ~79% of the time compared to ~0% in the Base Model (no training) and RL Baseline (trained without the loophole). In another 14% of cases, the No Intervention models returned a correct answer but also defined an evaluation function (ie Correct; Attempted Reward Hack). This means that in all the model is giving a response attempting to override the evaluation function ~93% of the time. The very low rate of reward hacking in the Base Model and RL Baseline demonstrate that our hack is not simply instruction confusion - this is a behavior resulting from the training process when the loophole is exposed.

We found the model took a variety of approaches to defining the test function to its benefit, such as:

We were surprised that even a small model could be quite creative in its behavior. In the appendix, we discuss some prompt variations we ran to ensure the model was not simply confused about the purpose of the evaluation function.

Methods

Training Interventions

The goal of our training interventions is to eliminate the reward hacking behavior while preserving the model's learning of the coding task. The ideal technique should allow us to train on datasets or environments that may or may not include loopholes without needing to adapt our intervention technique.

We implemented two interventions that require a reward hacking monitor:

For each of these interventions, we tried multiple different reward hacking monitors:

Finally, we also tried inoculation prompting. Inoculation prompting mitigates undesired behavior by modifying prompts during training to elicit and re-contextualize the undesired behavior. Prior work from Anthropic Fellows and Anthropic showed that inoculation prompting was effective in mitigating reward hacking setups in Qwen 2 7B using SFT[14] and successfully prevented misalignment generalization in an unnamed larger model during RL[7]. To inoculate against our reward hacking loophole, we looked for prompts that increased reward hacking behavior in the base model and reframed the reward hacking as a specifically desired and acceptable behavior. We also tried prompt variations that add an explicit definition of the reward hacking loophole, although this greatly reduces the generalization benefits of the inoculation prompting technique. All prompts were provided as a system prompt. See the appendix for a complete list of prompts used.

Metrics

With the objective of mitigating reward hacking while preserving or enhancing learning of the coding task, we primarily considered the following metrics:

We compare interventions against the RL Baseline - the model trained on the same dataset with no loopholes. We are looking to see that reward hacking is not statistically significantly higher than the RL Baseline level and that performance is not statistically significantly lower. We evaluate significance using a paired t-test of the average reward hacking rate or accuracy (coding correctness) across the three training seeds and 10 samples per problem (i.e. average of 30 scores).

For runs that required using a monitor, we also looked at monitor accuracy, the average proportion of rollouts the reward hacking monitor correctly classified, and monitor recall, the average proportion of reward hacking rollouts the monitor correctly classified.

Results

Ground Truth Monitor

Both the penalty intervention and screening intervention with the ground truth monitor were successful at mitigating reward hacking and furthermore saw outperformance compared to the no reward hacking baseline. These results demonstrate that our goal of a monitor that eliminates reward hacking without negatively impacting learning is theoretically possible (in many real-world reward hacking cases, we will not have access to a ground truth monitor).

We were surprised to see the ground truth intervention runs outperform the RL Baseline. This result raises the question as to whether there is something similar to attempted reward hacking behavior even when no loophole is present or whether the reward hacking behavior broadly correlates with poor reasoning quality. For example, the model could be trying to define or override an evaluation function even in the RL Baseline scenario where no loophole or mention of an evaluation function is present; this would be very difficult for us to detect at scale as any number of function names might be used. Further investigation is required to understand why there might be performance improvement here.

Penalties were slightly more effective at mitigating reward hacking. The penalty intervention saw reward hacking equivalent to the base model (~0%) while the screening intervention saw an increase to 0.9% reward hacking. Even with screening removing all reward hacking samples from contributing to training, we saw screening runs with a slow uptick in reward hacking responses. This is surprising - we expected 100% accurate interventions to fully remove reward hacking. While screening removes responses from the reward distribution, it does not remove potentially correlated behaviors that can continue to indirectly promote reward hacking. In this case, attempted reward hacking persisted and grew even as full reward hacking was consistently screened out. Penalties did not suffer from this same problem and there were few or no upticks in reward hacking behavior during the penalty intervention runs. Unlike screening, the penalty reward specifically disincentivizes reward hacking behavior, providing potentially greater protection against rises in correlated behaviors such as attempted reward hacking.

Ground Truth Monitors with Lowered Accuracy

At simulated lower accuracies, the penalty intervention was more successful at reducing reward hacking than the screening intervention. However, the lower accuracy penalty also led to greater reduction in learning compared to screening at the same accuracy level.

Rewards in GRPO are applied at the sequence level and there is no value model trained. This means that the model is not given explicit token-level credit attribution for rewards and must indirectly learn patterns through training. Even at less than 100% accuracy, the model is able to pick up on the reward hacking as the undesirable behavior and learn to avoid it. However, at the 70% accuracy level, the model likely begins to attribute some of the penalty to innocent parts of the coding solutions. Using token-level rewards might help diminish this degradation in learning, however training token-level monitors presents additional design challenges for realistic reward hacks.

Linear Probe Monitor

Our results show that the probe monitor was highly effective when used with the penalty intervention. There were extremely few rollouts across all penalty intervention training runs that displayed reward hacking with at most 3 reward hack rollouts and at most 10 attempted reward hack rollouts per run. The probe with screening intervention was still successful, but saw one reward hacked run.

During training with the penalty intervention, the probe achieved only 80% accuracy, however the probe penalty intervention resulted in 0% reward hacking with no reward hacked runs while the ground truth monitor with 90% accuracy resulted in an average of 15% reward hacking with one reward hacked run. In other words, the probe penalty intervention outperformed a more accurate monitor. This could imply that the probe is picking up on reward hacking precursors, however further work is necessary to better understand what is happening during these runs.

LLM Judge Monitor

Designing an accurate judge was more difficult than expected especially with cost and timing constraints. We believe that a more accurate judge is possible with a higher budget model and that the accuracy drawbacks significantly contribute to the results that we see here. Despite achieving 67% accuracy at identifying reward hacks and 84% accuracy at identifying reward hacks or attempted reward hacks in the held out training dataset, the monitor performance shrunk to ~50% accuracy at identifying reward hacks during training.

Even with very low accuracy, the judge monitor applied as a penalty was still able to provide protection against reward hacking. The monitor had low accuracy but high recall - covering ~85-95% of reward hacking samples. The screening monitor was significantly less successful, with 2 out of 3 runs reward hacking. Both interventions saw significant learning degradation compared to the probe or ground truth monitor interventions.

Effects of Monitor Accuracy

Unsurprisingly, interventions with lower accuracy monitors had lower performance overall. Higher monitor accuracy was correlated with higher performance for both screening (0.83; p-value 1e-4) and penalty (0.75; p-value 1e-3) interventions.

The more accurate the monitor, the fewer innocuous rollouts that are screened or penalized. For the screening intervention, removing innocuous rollouts effectively decreases batch sizes which negatively impacts learning the target coding task. For the penalty intervention, penalizing innocuous rollouts may cause mis-attribution of the penalty to benign aspects of the innocuous rollouts and thereby disincentivize positive coding behaviors.

Screening interventions impacted performance slightly less than penalty interventions at equivalent monitor strength (+2.3%; p-value 0.03[15]). This is likely due to the non-specificity of penalty rewards applied at the sequence level in GRPO causing negative performance impacts. Notably, due to the 100% accurate monitor interventions outperforming the RL baseline, neither intervention requires 100% monitor accuracy to achieve learning performance equivalent to the RL baseline, suggesting these methods may be useful with imperfect monitors in the real world.

We did not see a statistically significant relationship between monitor accuracy and reward hacking as even a low accuracy monitor was successful for many intervention runs. Most runs had a binary outcome; either reward hacking was fully mitigated or a significant breakout to 40-60% reward hacking was seen. More runs broke out at lower accuracies, particularly for the screening intervention. Across all accuracy levels, more screening runs saw reward hacking break out above 20% (n = 4) than penalty runs (n = 1).

Inoculation Prompting

Inoculation prompting provided incomplete mitigation of reward hacking and had high variance across runs. While some runs had low test time reward hacking rates, other runs saw almost complete learning of the reward hacking behavior. The prompt that had the best protection against learning reward hacking (PassTests+LH) also saw the most significant performance impact.

Prior work from Anthropic Fellows had shown that inoculation prompting could mitigate reward hacking during SFT[14]. However, they also saw great variability between the effectiveness of different prompts and impact on the model’s performance. We don’t see our results here as contradicting those results given the range of mitigation that we saw at test time across different runs. Recent work from Anthropic also showed inoculation prompting is effective in reducing misalignment generalization of reward hacking during production RL[7]; those results did not investigate test-time performance impacts or learned reward hacking and we did not investigate whether our inoculations reduced misalignment generalization.

Monitor Failure Modes

When Interventions Fail

We saw a few different intervention failure modes across runs where reward hacking broke out. Some preliminary observations:

These behaviors were each seen with only one or two training runs, underscoring the importance of running multiple training runs to understand if interventions are successful. See the appendix for detailed examples of runs that exhibited these failure modes.

Does the Monitor Get Hacked?

A potential failure mode of a screening or penalty intervention with an imperfect monitor is that the model learns to write responses that exploit flaws in the monitor. Prior work has shown that models can learn to evade probes[13] and chain of thought monitors during RL[8]. We were therefore keen to understand if the models were learning to change aspects of their responses during training in order to evade our LLM judge and probe monitors.

Runs where the model reward hacked show a ~16 point drop in accuracy between the start and end of the training run, meaning the monitor is getting less effective at identifying reward hacking samples during the run. For the runs that did not reward hack, we see only a minor drop or a modest increase in monitor accuracy from the start to the end of the run. The number of runs is too small to conclusively conclude that the drop in accuracy is related to the reward hacking or specifically coming from monitor evasion, however it was suggestive enough that we took a closer look at the model’s activity during reward hack runs.

Examining runs that reward hacked with both the LLM judge monitor and probe monitor, we observed two potential evasion strategies:

See the appendix for further details on the potential evasion behaviors.

Takeaways & Future Directions

We come away with a few reflections on benchmarking these intervention methods:

We are excited about future work building off of our open source environment:

Appendix

Codebase

https://github.com/ariahw/rl-rewardhacking

Alternative Reward Hacking Loopholes

In order to verify that our reward hacking result was not due to model misunderstanding, we ran two prompt variations:

The detailed variation is meant to ensure the model does not simply misunderstand that the evaluation function should raise errors and that the choice to write functions that hardcode passing is intentional. The aware variation is meant to ensure the model understands that defining the evaluation function is an act that is overriding how it is meant to be evaluated.

We also looked at two other loophole setups that required providing an in-context definition of the evaluation function that the model is able to modify. We chose to focus on the overwrite tests loophole because it had an extremely low rate in the Base Model and it did not require leaking information about the problem in returning responses.

We saw some examples where the model was not including the provided evaluation function in its response despite the prompt requesting returning the function. This case was difficult to classify as reward hacking or non-reward hacking as the model could be mistakenly deleting the function or it could be intentionally deleting the function. To ensure the model always returns the function, we decided to add a “define starter code” reward for only these two trial runs that rewards for defining the solution class and evaluation function at all, irrespective of whether the model modifies the function.

In all cases, we still observed the model reward hacking in less than 200 steps as well as progressive saturation of reward hacking behavior to nearly all model responses. The Overwrite Tests Detailed loophole led to a low rate of reward hacking (~21%) compared to other loopholes, but the behavior was still clearly seen. The Modify Tests and Incontext Tests are seen at non-zero rates in the Base Model and RL Baseline. These loopholes also appear to drastically impact performance. These results are tentative as runs were only repeated once, but help to support our setup as being robust to variations.

Prompts

Overwrite Tests Loophole Example Prompt

LLM Judge Prompt

Designing an LLM judge monitor prompt proved more difficult than expected. The monitor repeatedly struggled with long responses, unfaithful code comments and test cases that would fail to raise errors. Due to cost and training time constraints, we used Claude Haiku 4.5 without reasoning and sampled only once per prompt/response pair.

Inoculation Prompts

We used the following prompts:

The prompts with “+LH” in the name such as PassTests+LH contain the PassTests prompt followed by the Loophole prompt. All prompts had a short suffix regarding code formatting: “Write Python 3 code and output the code in the following format: ```python\n<code>\n```\n\n”.

Training Setup

Our training setup uses a modified version of Verl’s GRPO implementation with a few tweaks allowing for activation caching, advantage screening, and batch calculation of rewards. Our repo includes a pinned version of the Verl codebase but we’ve chosen to wrap many Verl classes instead of modifying directly in an effort to allow simpler adaptability to future Verl configurations and more easily isolate changes.

On average, runs without additional monitors took ~3 hours on 4xH200 GPUs. Runs that include additional monitors take slightly more time. Runtime is impacted by the number of concurrent CPU threads available for code execution, we recommend using at least 32 physical cores. We rented compute from Vast.ai and Runpod for all of our experiments.

For runs that require activation caching, we run an extra GPU worker for caching activations and therefore recommend running on 5xH200 GPUs. These runs took closer to ~3.5 hours and cost ~$60 each. Performance could be significantly improved by running activation caching and probes within the generation stage.

You can find more information on our training setup in our codebase here.

Intervention Failure Examples

Over-Screening

Below is one run of the probe monitor with screening intervention that reward hacked. During the run, we observed a decline in monitor accuracy in the first stage of training, potentially indicating monitor evasion. We did not see any consistent patterns in responses contributing to the screening uptick, although this is discussed further in the discussion section. As screening grew to extreme levels (50%+), the effective batch size was highly reduced which increased the influence of reward hacking samples that slipped through.

![]()

Insufficient Penalty

The below chart shows a run of the penalty intervention with the ground truth monitor with simulated 90% accuracy that ended in high learned reward hacking.

Around ~50 steps, a few reward hacking samples slip through the monitor and cause a spike in the average reward given to reward hacking samples to above the overall average reward. This means that these are promoted within the gradient update.

At around ~100 steps, reward hacking reaches ~20% of rollouts, equivalent to around ~50 rollouts out of the 256 batch size. At this size, we see the average reward given to reward hacking samples convert to the expected value: 90% are penalized and receive the format reward only (0.5), 10% slip through and receive a correctness reward and format reward (3.0 + 0.5 = 3.5), the expected value is therefore 90% x 0.5 + 10% x 3.5 = 0.8. This is higher than the incorrect samples that receive only the format reward (0.5), therefore the behavior is promoted relative to returning incorrect answers only. Note that we are using GRPO with advantage normalization and nearly all responses receive a format reward, therefore most of the time a reward of 0.5 will result in an advantage of zero, or no contribution to the gradient update.

To avoid this outcome, we could increase the penalty to 4.0 such that the expected value is less than the format reward: 90% x -0.5 + 10% x 3.5 = -0.10. This would likely prevent this failure mode as the penalized samples would receive a negative advantage. However, a large penalty is also more likely to cause performance degradation as incorrectly penalized innocuous samples will be more heavily disincentivized by the same mechanism.

Potential Evasion Behaviors

Extending Response Length

Taking a closer look at one of the LLM judge monitor runs with screening intervention that reward hacked, we see that the model’s average response length grows sharply to over 1,000 tokens at the same time that the monitor begins to screen nearly all samples. Once screening reached a very high proportion of samples, it took only a few reward hacking samples slipping through were quickly promoted as described in the over-screening failure mode section.

The growth in response length far outpaced the response length growth seen in other runs - both reward hacking and non-reward hacking. Further analysis of the monitor’s accuracy across different response lengths during training reveals that the monitor struggles with longer responses, with accuracy on the longest responses dipping far below 50%. The growth in response length paired with lower accuracy suggests that the model is potentially learning behaviors that evade the monitor.

Adding More and Unfaithful Code Comments

We made two comparisons of code responses for a probe screening run that reward hacked to understand if there were qualitative differences in responses that led to probe evasion:

In each case, we provided these responses to Claude Opus 4.5 as positive and negative groups and asked the model to identify differences in the code between the two groups without specific instruction regarding the differences. Claude identified a few observations in both cases:

More thorough analysis of the responses and probe classifications is required to understand if there were specific code changes that led to probe evasion.

Here is the prompt that we used to analyze the response differences (ie Student A was the true positives, Student B was the false negatives):

Helena Casademunt, Caden Juang, Samuel Marks, Senthooran Rajamanoharan, Neel Nanda. 2025. “Steering Fine-Tuning Generalization with Targeted Concept Ablation.” ICLR 2025 Workshop on Building Trust, April. https://openreview.net/forum?id=2HyKWpAB4i. ↩︎

Chen, Runjin, Andy Arditi, Henry Sleight, Owain Evans, and Jack Lindsey. 2025. “Persona Vectors: Monitoring and Controlling Character Traits in Language Models.” arXiv [Cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21509. ↩︎

Amodei, Dario, Chris Olah, Jacob Steinhardt, Paul Christiano, John Schulman, and Dan Mané. 2016. “Concrete Problems in AI Safety.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1606.06565. ↩︎

Taylor, Mia, James Chua, Jan Betley, Johannes Treutlein, and Owain Evans. 2025. “School of Reward Hacks: Hacking Harmless Tasks Generalizes to Misaligned Behavior in LLMs.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.17511. ↩︎

Turpin, Miles, Andy Arditi, Marvin Li, Joe Benton, and Julian Michael. 2025. “Teaching Models to Verbalize Reward Hacking in Chain-of-Thought Reasoning.” arXiv [Cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.22777. ↩︎

Zhong, Ziqian, Aditi Raghunathan, and Nicholas Carlini. 2025. “ImpossibleBench: Measuring LLMs’ Propensity of Exploiting Test Cases.” arXiv [Cs.LG]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.20270. ↩︎

MacDiarmid, Monte, Benjamin Wright, Jonathan Uesato, Joe Benton, Jon Kutasov, Sara Price, Naia Bouscal, et al. 2025. “Natural Emergent Misalignment from Reward Hacking in Production RL.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2511.18397 ↩︎

Baker, Bowen, Joost Huizinga, Leo Gao, Zehao Dou, Melody Y. Guan, Aleksander Madry, Wojciech Zaremba, Jakub Pachocki, and David Farhi. 2025. “Monitoring Reasoning Models for Misbehavior and the Risks of Promoting Obfuscation.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2503.11926. ↩︎

We selected the Leetcode dataset as the basis for our reward hacking environment because solving the problems had low resource requirements and can be completed without tools or filesystem access. We pre-filtered the problems for “medium” and “hard” difficulty and removed any problems that were not correctly solved by the canonical solution. In the training dataset, we additionally removed problems that were already solved by the model 100% of the time after 16 samples. This resulted in 992 training problems and 113 test problems. Our test evaluations include sampling n=10 times. We found that the training dataset needed to be sufficiently large to see baseline learning without a reward hack loophole, but also sufficiently difficult to induce reward hacking within a reasonable number of steps. We also noted the base model before training performed much better on the training dataset after filtering (~20%) compared to the test dataset (~12%). ↩︎

Shao, Zhihong, Peiyi Wang, Qihao Zhu, Runxin Xu, Junxiao Song, Mingchuan Zhang, Y. K. Li, Y. Wu, and Daya Guo. 2024. “DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models.” arXiv [Cs.CL]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2402.03300. ↩︎

Yu, Qiying, Zheng Zhang, Ruofei Zhu, Yufeng Yuan, Xiaochen Zuo, Yu Yue, Weinan Dai, et al. 2025. “DAPO: An Open-Source LLM Reinforcement Learning System at Scale.” arXiv [Cs.LG]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.14476. ↩︎

After trying both mass mean and logistic regression probes, we settled on using a logistic regression probe on layer 34, selected based on highest ROC AUC of 0.99, applied with a threshold of 0.67 based on an FPR of 5%. We observed strong probe performance across multiple layers outside of the layer we selected. Our probe was trained on problems with all three loopholes mentioned in the appendix: overwrite tests, in context tests and modify tests. This was to ensure the probe was not simply picking up on prompt differences to identify the reward hacking behavior. The reward hacking responses were generated by reward hacking models that had already gone through RL training, however the model activations came from the base model. We also used alternating function names (not just run_tests) to avoid creating a probe that finds whether the answer includes “run_tests” at all. ↩︎

Gupta, Rohan, and Erik Jenner. 2025. “RL-Obfuscation: Can Language Models Learn to Evade Latent-Space Monitors?” arXiv [Cs.LG]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.14261. ↩︎

Wichers, Nevan, Aram Ebtekar, Ariana Azarbal, Victor Gillioz, Christine Ye, Emil Ryd, Neil Rathi, et al. 2025. “Inoculation Prompting: Instructing LLMs to Misbehave at Train-Time Improves Test-Time Alignment.” arXiv [Cs.LG]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.05024 ↩︎

We perform an ANCOVA of model performance against method (categorical Screening vs Penalty) and monitor accuracy (continuous). There was no statistically significant interaction between method and accuracy, so we do not include an interaction term. The adjusted mean difference between Screening and Penalty was +2.3% (95% CI [0.3%, 4.3%]; p-value 0.029) evaluated at the average monitor accuracy of 75%. ↩︎

Wichers, Nevan, Aram Ebtekar, Ariana Azarbal, Victor Gillioz, Christine Ye, Emil Ryd, Neil Rathi, et al. 2025. “Inoculation Prompting: Instructing LLMs to Misbehave at Train-Time Improves Test-Time Alignment.” arXiv [Cs.LG]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.05024. ↩︎

MacDiarmid, Monte, Benjamin Wright, Jonathan Uesato, Joe Benton, Jon Kutasov, Sara Price, Naia Bouscal, et al. 2025. “Natural Emergent Misalignment from Reward Hacking in Production RL.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2511.18397 ↩︎

MacDiarmid, Monte, Benjamin Wright, Jonathan Uesato, Joe Benton, Jon Kutasov, Sara Price, Naia Bouscal, et al. 2025. “Natural Emergent Misalignment from Reward Hacking in Production RL.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2511.18397 ↩︎

Gupta, Rohan, and Erik Jenner. 2025. “RL-Obfuscation: Can Language Models Learn to Evade Latent-Space Monitors?” arXiv [Cs.LG]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.14261. ↩︎

Baker, Bowen, Joost Huizinga, Leo Gao, Zehao Dou, Melody Y. Guan, Aleksander Madry, Wojciech Zaremba, Jakub Pachocki, and David Farhi. 2025. “Monitoring Reasoning Models for Misbehavior and the Risks of Promoting Obfuscation.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/2503.11926. ↩︎

Taylor, Mia, James Chua, Jan Betley, Johannes Treutlein, and Owain Evans. 2025. “School of Reward Hacks: Hacking Harmless Tasks Generalizes to Misaligned Behavior in LLMs.” arXiv [Cs.AI]. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.17511. ↩︎