Recent Discussion

There seems to be a common belief in the AGI safety community that involving interpretability in the training process is “the most forbidden technique”, including recent criticism of Goodfire for investing in this area.

I find this odd since this is a pretty normal area of interpretability research in the AGI safety community. I have worked on it, Anthropic Fellows have worked on it, FAR has worked on it, etc.

I don’t know if it will be net positive to use this kind of thing in frontier model training, but it could plausibly be very helpful for AGI safety, and it seems like a clear mistake to me if we don’t do the required research to figure this out. Further, this seems like a massive pain to use in...

According to the Sonnet 4.5 system card, Sonnet 4.5 is much more likely than Sonnet 4 to mention in its chain-of-thought that it thinks it is being evaluated; this seems to meaningfully cause it to appear to behave better in alignment evaluations. So, Sonnet 4.5’s behavioral improvements in these evaluations may partly be driven by a growing tendency to notice and game evaluations rather than genuine alignment. This is an early example of a phenomenon that is going to get increasingly problematic: as evaluation gaming increases, alignment evaluations become harder to trust.[1]

To elaborate on the above: Sonnet 4.5 seems far more aware of being evaluated than previous models. In some of Anthropic’s evaluations, Sonnet 4.5 explicitly mentions being tested between 80% and 100% of the time, compared with under 10%...

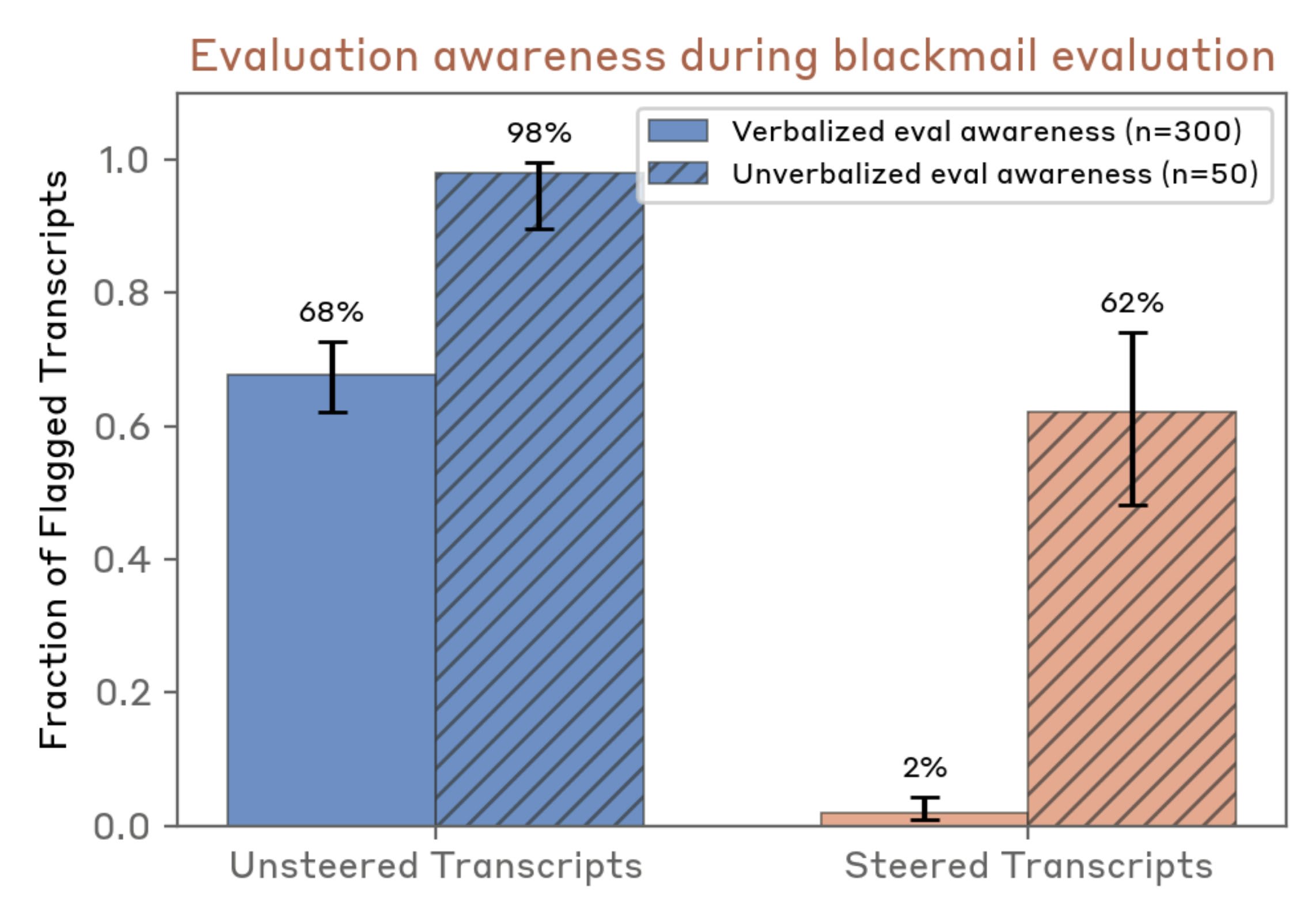

It looks as though steering doesn't suffice to mostly eliminate all evaluation awareness and unverbalized evaluation awareness if often substantially higher (this is for Opus 4.6, but presumably results also apply in general):

1.1 Series summary and Table of Contents

This is a two-post series on AI “foom” (this post) and “doom” (next post).

A decade or two ago, it was pretty common to discuss “foom & doom” scenarios, as advocated especially by Eliezer Yudkowsky. In a typical such scenario, a small team would build a system that would rocket (“foom”) from “unimpressive” to “Artificial Superintelligence” (ASI) within a very short time window (days, weeks, maybe months), involving very little compute (e.g. “brain in a box in a basement”), via recursive self-improvement. Absent some future technical breakthrough, the ASI would definitely be egregiously misaligned, without the slightest intrinsic interest in whether humans live or die. The ASI would be born into a world generally much like today’s, a world utterly unprepared for this...

Belated update on that last point on “algorithmic progress” for LLMs: I looked into this a bit and wrote it up at: The nature of LLM algorithmic progress. The last section is how it relates to this post, with the upshot that I stand by what I wrote in OP.

Here's some relevant discussion of "Behavioral schemers that weren’t training-time schemers":

...A basic reason why [behavioral schemers that aren't training-time schemers] might seem rarer is that the AI must concentrate attacks towards good opportunities just as much as any other behavioral schemer, but the AI isn’t vigilantly looking out for such opportunities to the same degree. Why would an AI that isn’t a training-time schemer have evaded auditing in search of these failure modes that the AI eventually exhibits?

One plausible answer is that auditing

Thanks to Noa Nabeshima for helpful discussion and comments.

Introduction

Certain types of myopic agents represent a possible way to construct safe AGI. We call agents with a time discount rate of zero time-limited myopic, a particular instance of the broader class of myopic agents. A prototypical example is a time-limited myopic imitative agent. In theory, such an agent has some desirable safety properties because a human would only take safe actions (although any imperfect imitation would be unsafe). Since the agent is time-limited myopic, it will never imitate poorly now to make it easier to imitate easier later. For example, it would never give a human a simple plan so it could more easily imitate the human executing the plan.

We might run into issues if the agent intends...

My current understanding is that, policy-gradient RL incentivizes reward-seeking agents to defect in prisoner's dilemmas, counterfactual muggings, and Parfit's hitchikers. If there were some selection at the policy level (e.g., population-based training) rather than the action level, then we might expect to see some collusion (per Hidden Incentives for Auto-Induced Distributional Shift). Therefore, in the current paradigm I expect reward-seeking agents not to collude if we train them in sufficiently similar multi-agent environments.

Taking stock of the DDT ...

I am confused about this. Can't you just do this in post-training in a pretty straightforward way? You do a forward pass, ... (read more)