3 Answers sorted by

50

I think past acceleration is mostly about a large number of improvements that build on one another rather than a small number of big wins (as Katja points out), and future acceleration will probably be more of the same. It seems like almost all of the tasks that humans currently do could plausibly be automated without "AGI" (though it depends on how exactly you define AGI), and if you improve human productivity a bunch in enough industries then you are likely to have faster growth.

I expect "21st century acceleration is about computers taking over cognitive work from humans" will be the analog of "The industrial revolution is about engines taking over mechanical work from humans / beasts of burden."

From that perspective, asking "What technology short of AGI would take over cognitive work from humans, and how?" is analogous to asking "What technology short of a universal actuator would take over mechanical work from humans, and how?" The answer is just: a bunch of stuff that's specific to the details of each type of work.

Thoughts on some particular technologies, kind of at random:

- I think that most of that automation is likely to involve new software, and so the size of the software industry is likely to grow a bunch. Increasing productivity in the software industry (likely via ML) would then be an important driver of productivity growth despite software currently being a small share of GDP.

- I think that cheap solar power, automation of manufacturing and construction (including manufacturing industrial tools and construction of factories), and automation of service jobs are also very important stories.

- I think that west probably could be growing considerably faster even without qualitative technological change, so part of the story may be western countries either getting out of their current slump or being overtaken.

The other part of your post is about how much qualitative change would correspond to a doubling of growth rates. I think you are moderately underestimating the extent of historical acceleration and so overestimating how much qualitative change would be needed:

- I think the US over the last 200 years is a particularly bad comparison because at the beginning of the period it was benefiting a lot from colonization. Below I talk about the UK which I think is probably more representative. I chose the UK as the the most natural frontier economy after the industrial revolution, but I expect the exercise would be similar for other countries without complications.

- Looking at growth over the last 200 years hides the fact that there was a period of more rapid acceleration followed by a stagnation. If we instead compared 1800 to 1950 we'd see a larger change in growth rates accompanied by a smaller qualitative change. So that's probably more useful if you are looking for an existence proof (and I think low levels of current growth likely make acceleration easier).

In 1800 the US was growing rapidly in significant part because colonists were still taking new land and then increasing utilization of that land. So over the last 200 years you have a decrease in some kinds of growth and an increase in others. I don't know much about this and it may be completely wrong, but given that the US was growing so much faster than the rest of the world and that there's such a simple explanation that seems to check out, that's what I'd assume is going on. If that's right then it can still be OK to use the US as an example but you can't use raw growth numbers to infer something about technological change.

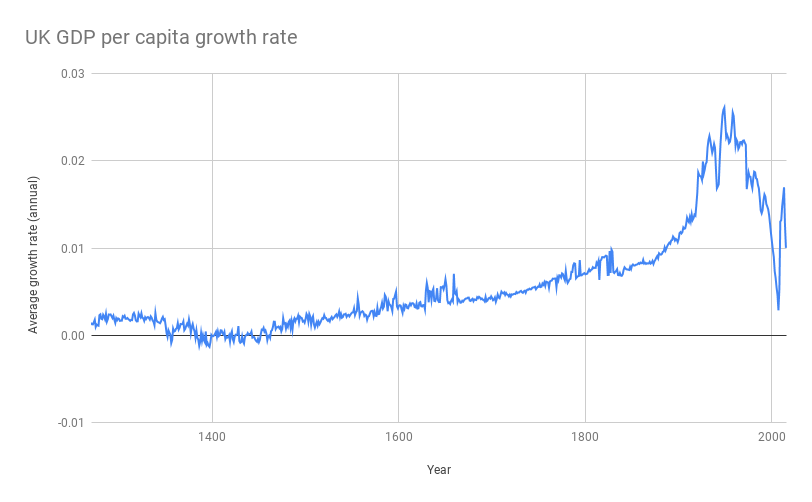

If you want to see what's happening in frontier economies since the industrial revolution then it seems more natural to use something like per capita GDP in the UK. If I look up the GDP per capita in the UK time series at Our World in Data and turn that into a graph of (GDP per capita growth rate) vs (time), I get:

So it seems to me like things really did change a lot as technology improved, growing from 0.4% in 1800-1850, to 1% in 1850-1900, to .8% in 1900-1950, to 2.4% in 1950-2000. What we're talking about is a further change similar in scope to the change from 1800 to 1850 or from 1900 to 1950.

(I don't know if there are other reasons the UK isn't representative. I think the most obvious candidate would be that 1900-1950 was a really rough period for the UK, and then 1950-2000 potentially involves some catch-up growth.)

Thanks! This is my new favorite answer. I consider it to be a variant on Abram's answer.

--I think the large number of small improvements vs. small number of large improvements thing is a red herring, a linguistic trick as you say. There's something useful about the distinction for sure, but I don't think we have any major disagreements here.

-- Re: "21st century acceleration is about computers taking over cognitive work from humans" will be the analog of "The industrial revolution is about engines taking over mechanical work f...

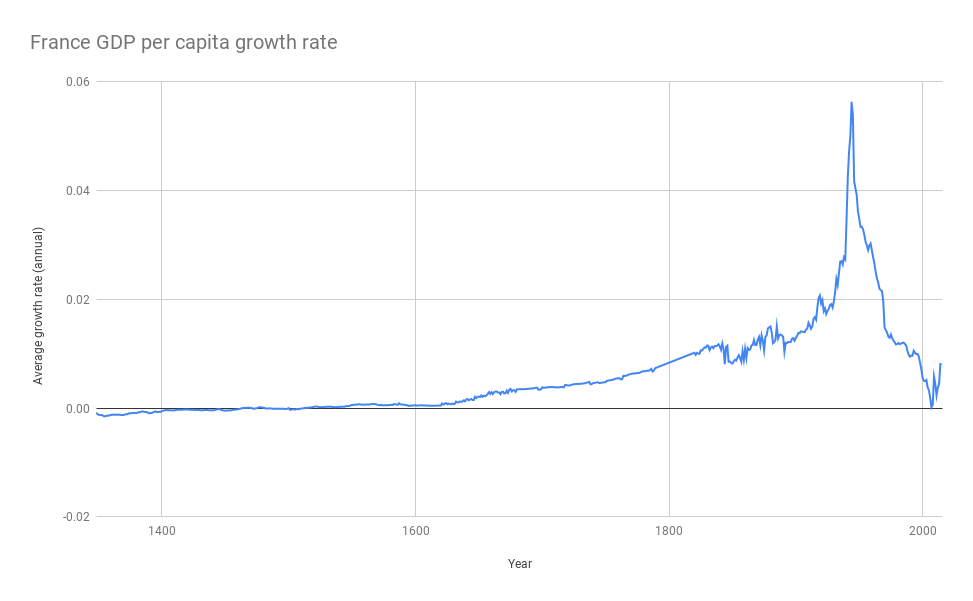

France is the other country for which Our World in Data has figures going back to 1400 (I think from Maddison), here's the same graph for France:

There is more crazy stuff going on, but broadly the picture looks the same and there is quite a lot of acceleration between 1800 and the 1950s. The growth numbers are 0.7% for 1800-1850, 1.2% for 1850-1900, 1.2% for 1900-1950, 2.8% for 1950-2000.

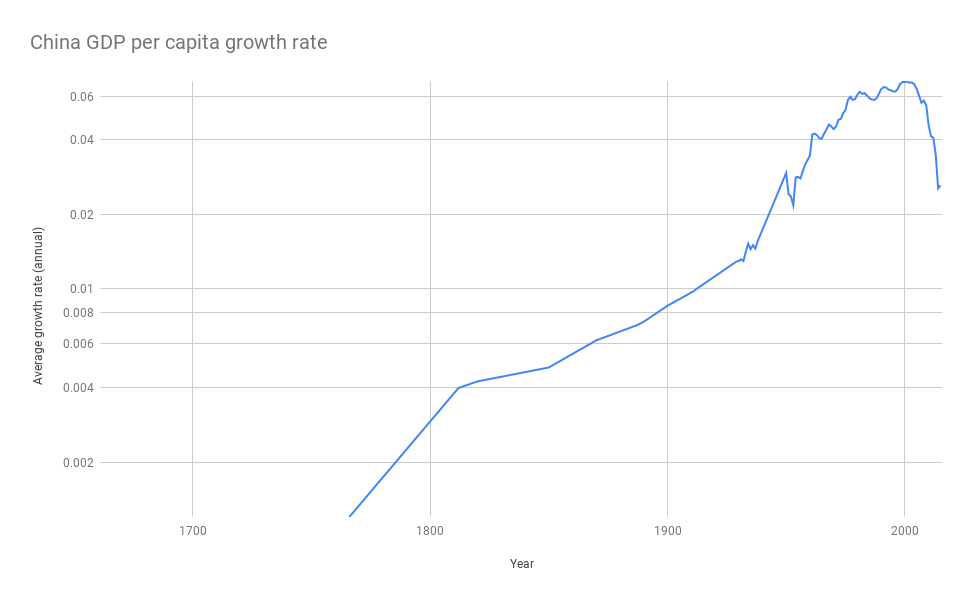

And for the even messier case of China:

Growth averages 0 from 1800 to 1950, and then 3.8% from 1950-2000 and 6.9% from 2000-2016.

40

I don't know what post to link to, but I recall at some point Robin Hanson articulated fully automated manufacturing as his guess about the next big bump in GDP doubling times.

The argument as I recall it:

- Full automation means automation of everything including building the factories themselves.

- Full automation plausibly requires advanced AI, but not full human-level AGI. So (especially if we believe in relatively slow AI progress) we might expect to see this significantly before an AGI-based boom.

- Fully automated manufacturing would make manufacturing much cheaper by cutting out the human cost, and automated manufacture of factories would allow rapid scaling, and rapid responses to economic demands, which would be dramatic and game-changing. Production cycles (from idea to prototype to hitting the market) would be dramatically shortened.

Thanks, this is my favorite answer so far. [EDIT: Now Paul's is my favorite.] It's sorta what I had in mind with my list of candidates above. I guess your points #2 and #3 are the ones I'm skeptical of.

Re point 2: If we've automated everything, including building factories and entire production cycles, (a) doesn't that involve figuring out how to make computers do a huge variety of tasks, many of which are quite intellectually difficult, such that plausibly the easiest way to do this is to create general AI rather than loads of na...

30

Excluding AI, and things like human intelligence enhancement, mind uploading ect.

I think that the biggest increases in the economy would be from more automated manufacturing. The extreme case is fully programmable molecular nanotech. The sort that can easily self replicate and where making anything is as easy as saying where to put the atoms. This would potentially lead to a substantially faster economic growth rate than 9%.

There are various ways that the partially developed tech might be less powerful.

Maybe the nanotech uses a lot of energy, or some rare elements, making it much more expensive.

Maybe it can only use really pure feedstock, not environmental raw materials.

Maybe it is just really hard to program, no one has built the equivalent of a compiler yet, we are writing instructions in assembly, and even making a hello world is challenging.

Maybe we have macroscopic clanking replicators.

Maybe we have a collection of autonomous factories that can make most, but not all, of their own parts.

Maybe the nanotech is slowed down by some non-technological constraint, like bureaucracy, proprietary standards and patent disputes.

Mix and match various social and technological limitations to tune the effect on GDP

Some people think GDP is a good metric for AI timelines and takeoff speeds, and that the world economy will double in 4 years before the start of the first 1-year doubling period, and that AGI will happen after the economy is already growing much faster than it is today.

Other than AGI, what technologies could significantly accelerate world GDP growth? (Say, to a doubling period of <8 years, meaning the whole world economy grows 9%+ per year, significantly faster than the fastest-growing countries today.)

I find myself struggling to think of plausible answers to this question. Here are some ideas:

--Cheap energy, e.g. from solar panels or fusion

--Cheap resources, e.g. from asteroid mining, undersea mining, automated mines...

--Robots and self-driving cars make transportation and manufacturing cheaper

--3D printing? Idk.

--Narrow AI? Seems like the most plausible answer, but narrow AI doing what, exactly? Driving cars? Manufacturing things? Already discussed that. Inventing new products? OK, but in that case won't they also invent AGI?

My problem is that while all of these things seem like they could be a big deal by ordinary standards, they don't seem like that big a deal. Looking back over US economic history, it seems to my quick glance that growth rates haven't changed much in 200 years. (!!!) But over that time energy, resources, etc. have gotten lots cheaper in the USA, and all sorts of new tech has been developed. Worldwide, it looks like the last time annual GWP growth was less than half of what it is now (excluding the Great Depression) was... 1875! (At least according to my data, would love to see a more thorough investigation of this). The world looked hella different in 1875 than it does now in 2020; doubling world GDP growth rates again seems like a pretty tall order. I believe that AGI could do it, but what else could?