This post grew out of conversations with several people, including Daniel Kokotajlo, grue_slinky and Linda Lisefors, and is based in large part on a collection of scattered comments and blog-posts across lesswrong, along with some podcast interviews - e.g. here. The in-text links near quotes will take you to my sources.

I am attempting to distinguish two possibilities which are often run together - that progress in AI towards AGI (‘takeoff’) will be discontinuous and that it will be fast, but continuous. Resolving this distinction also addresses the claim that there has been a significant shift in arguments for AI presenting an existential risk: from older arguments discussing an ultra-fast intelligence explosion occurring in a single ‘seed AI’ to more moderate scenarios.

I argue that the ‘shift in arguments on AI safety’ is not a total change in basic assumptions (which some observers have claimed) but just a reduction in confidence about a specifically discontinuous takeoff. Finally, I try to explicitly operationalize the practical differences between discontinuous takeoff and fast, continuous takeoff.

Further Reading

Summary: Why AI risk might be solved without additional intervention from Longtermists

Paul Christiano’s original post

MIRIs Thoughts on Discontinuous takeoff

Misconceptions about continuous takeoff

Soft Takeoff can still lead to Decisive Strategic Advantage

Defining Discontinuous Progress

What do I mean by ‘discontinuous’? If we were to graph world GDP over the last 10,000 years, it fits onto a hyperbolic growth pattern. We could call this ‘continuous’ since it is following a single trend, or we could call it ‘discontinuous’ because, on the scale of millennia, the industrial revolution exploded out of nowhere. I will call these sorts of hyperbolic trends ‘continuous, but fast’, in line with Paul Christiano, who argued for continuous takeoff, defining it this way:

AI is just another, faster step in the hyperbolic growth we are currently experiencing, which corresponds to a further increase in rate but not a discontinuity (or even a discontinuity in rate).

I’ll be using Paul’s understanding of ‘discontinuous’ and ‘fast’ here. For progress in AI to be discontinuous, we need a switch to a new growth mode, which will show up as a step function in the capability of AI or in the rate of change of the capability of the AI over time. For takeoff to be fast, it is enough that there is one single growth mode that is hyperbolic or some other function that is very fast-growing.

The view that progress in AI will be discontinuous, not merely very fast by normal human standards, was popular and is still held by many. Here is a canonical explanation of the view, from Eliezer Yudkowsky in 2008. Compare this to the more recent ‘what failure looks like’ to understand the intuitive force of the claim that views on AI risk have totally changed since 2008.

Recursive self-improvement - an AI rewriting its own cognitive algorithms - identifies the object level of the AI with a force acting on the metacognitive level; it "closes the loop" or "folds the graph in on itself"...

...When you fold a whole chain of differential equations in on itself like this, it should either peter out rapidly as improvements fail to yield further improvements, or else go FOOM. An exactly right law of diminishing returns that lets the system fly through the soft takeoff keyhole is unlikely - far more unlikely than seeing such behavior in a system with a roughly-constant underlying optimizer, like evolution improving brains, or human brains improving technology. Our present life is no good indicator of things to come.

Or to try and compress it down to a slogan that fits on a T-Shirt - not that I'm saying this is a good idea - "Moore's Law is exponential now; it would be really odd if it stayed exponential with the improving computers doing the research." I'm not saying you literally get dy/dt = e^y that goes to infinity after finite time - and hardware improvement is in some ways the least interesting factor here - but should we really see the same curve we do now?

RSI is the biggest, most interesting, hardest-to-analyze, sharpest break-with-the-past contributing to the notion of a "hard takeoff" aka "AI go FOOM", but it's nowhere near being the only such factor. The advent of human intelligence was a discontinuity with the past even without RSI...

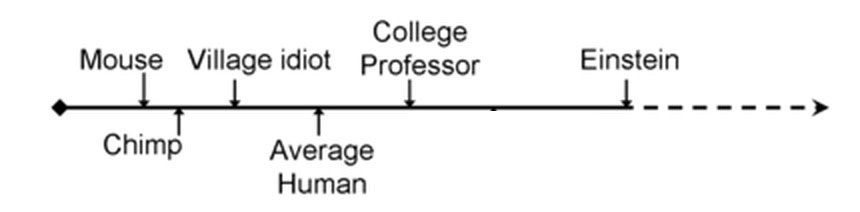

...which is to say that observed evolutionary history - the discontinuity between humans, and chimps who share 95% of our DNA - lightly suggests a critical threshold built into the capabilities that we think of as "general intelligence", a machine that becomes far more powerful once the last gear is added.

Also see these quotes, one summarizing the view by Paul Christiano and one recent remark from Rob Besinger, summarizing the two key reasons given above for expecting discontinuous takeoff, recursive self-improvement and a discontinuity in capability.

some systems “fizzle out” when they try to design a better AI, generating a few improvements before running out of steam, while others are able to autonomously generate more and more improvements.

MIRI folks tend to have different views from Paul about AGI, some of which imply that AGI is more likely to be novel and dependent on new insights.

I will argue that the more recent reduction of confidence in discontinuous takeoff is correct, but at the same time many of the ‘original’ arguments (e.g. those given in 2008 by Yudkowsky) for fast, discontinuous takeoff are not mistaken and can be seen as also supporting fast, continuous takeoff.

We should seriously investigate the continuous/discontinuous distinction specifically by narrowing our focus onto arguments that actually distinguish between the two: conceptual investigation about the nature of future AGI, and the practical consequences for alignment work of continuous/discontinuous takeoff.

I have tried to present the arguments in order from least to most controversial, starting with the outside view on technological progress.

There have been other posts discussing arguments for discontinuous progress with approximately this framing. I am not going to repeat their good work here by running over every argument and counterargument (See Further Reading). What I’m trying to do here is get at the underlying assumptions of either side.

The Outside View

There has recently been a switch between talking about AI progress being fast vs slow to talking about it as continuous vs discontinuous. Paul Christiano explains what continuous progress means:

I believe that before we have incredibly powerful AI, we will have AI which is merely very powerful. This won’t be enough to create 100% GDP growth, but it will be enough to lead to (say) 50% GDP growth. I think the likely gap between these events is years rather than months or decades.

It is not an essential part of the definition that the gap be years; even if the gap is rather short, we still call it continuous takeoff if AI progress increases without sudden jumps; capability increases following series of logistic curves merging together as different component technologies are invented.

This way of understanding progress as being ‘discontinuous’ isn’t uncontroversial, but it was developed because calling the takeoff ‘slow’ instead of ‘fast’ could be seen as a misnomer. Continuous takeoff is a statement about what happens before we reach the point where a fast takeoff is supposed to happen, and is perfectly consistent with the claim that given the stated preconditions for fast takeoff, fast takeoff will happen. It’s a statement that serious problems, possibly serious enough to pose an existential threat, will show up before the window where we expect fast takeoff scenarios to occur.

Outside view: Technology

The starting point for the argument that progress in AI should be continuous is just the observation that this is usually how things work with a technology, especially in a situation where progress is being driven by many actors working at a problem from different angles. If you can do something well in 1 year, it is usually possible to do it slightly less well in 0.9 years. Why is it ‘usually possible’? Because nearly all technologies involve numerous smaller innovations, and it is usually possible to get somewhat good results without some of them. That is why even if each individual component innovation follows a logistic success curve that is unstable between ‘doesnt work at all’ and ‘works’ if you were to plot results/usefulness against effort, progress looks continuous. Note this is what is explicitly rejected by Yudkowsky-2008.

When this doesn’t happen and we get discontinuous progress, it is because of one of two reasons - either there is some fundamental reason why the technology cannot work at all without all the pieces lining up in place, or there is just not much effort being put in, so a few actors can leap ahead of the rest of the world and make several of the component breakthroughs in rapid succession.

I’ll go through three illustrative examples of each situation - the normal case, the low-effort case and the fundamental reasons case.

Guns

Guns followed the continuous progress model. They started out worse than competing ranged weapons like crossbows. By the 15th century, the Arquebus arrived, which had some advantages and disadvantages compared to the crossbow (easier to use, more damaging, but slower to fire and much less accurate). Then came the musket, and later rifles. There were many individual inventions that went from ‘not existing at all’ to ‘existing’ in relatively short intervals, but the overall progress looked roughly continuous. However, the speed of progress still increased dramatically during the industrial revolution and continued to increase, without ever being ‘discontinuous’.

Aircraft

Looking specifically at heavier-than-air flight, it seems clear enough that we went from ‘not being able to do this at all’ to being able to do it in a relatively short time - discontinuous progress. The Wright brothers research drew on a few other pioneers like Otto Lilienthal, but they still made a rapid series of breakthroughs in a fairly short period: using a wind tunnel to rapidly prototype wing shapes, building a sufficiently lightweight engine, working out a method of control. This was possible because at the time, unlike guns, a very small fraction of human research effort was going into developing flight. It was also possible for another reason - the nature of the problem implied that success was always going to be discontinuous. While there are a few intermediate steps, like gliders, there aren’t many between ‘not being able to fly’ and ‘being able to fly’, so progress was unexpected and discontinuous. I think we can attribute most of the flight case to the low degree of effort on a global scale.

Nuclear Weapons

Nuclear Weapons are a purer case of fundamental physical facts causing a discontinuity. A fission chain reaction simply will not occur without many breakthroughs all being brought together, so even if a significant fraction of all the world’s design effort is devoted to research we still get discontinuous progress. If the Manhattan project had uranium centrifuges but didn’t have the Monte Carlo algorithms needed to properly simulate the dynamics of the sphere’s implosion, they would just have had some mostly-useless metal. It’s worth noting here that a lot of early writing about an intelligence explosion explicitly compares it to a nuclear chain reaction.

AI Impacts has done a far more thorough and in-depth investigation of progress along various metrics, confirming the intuition that discontinuous progress usually occurs where fundamental physical facts imply it - e.g. as we switch between different methods of travel or communication.

We should expect, prima facie, a random example of technological progress to be continuous, and we need specific, good reasons to think that progress will be discontinuous. On the other hand, there are more than a few examples of discontinuous progress caused either by the nature of the problem or differential effort, so there is not a colossal burden of proof on discontinuous progress. I think that both the MIRI people (who argue for discontinuous progress) and Christiano (continuous) pretty much agree about this initial point.

A shift in basic assumptions?

The argument has recently been made (by Will MacAskill on the 80,000 hours podcast) that there has been a switch from the ‘old’ arguments focussing on a seed AI leading to an intelligence explosion to new arguments:

Paul’s published on this, and said he doesn’t think doom looks like a sudden explosion in a single AI system that takes over. Instead he thinks gradually just AI’s get more and more and more power and they’re just somewhat misaligned with human interests. And so in the end you kind of get what you can measure

And that these arguments don’t have very much in common with the older Bostrom/Yudkowsky scenario (of a single AGI undergoing an intelligence explosion) - except the conclusion that AI presents a uniquely dangerous existential risk. If true, this would be a cause for concern as it would suggest we haven’t become much less confused about basic questions over the last decade. MacAskill again:

I have no conception of how common adherence to different arguments are — but certainly many of the most prominent people are no longer pushing the Bostrom arguments.

If you look back to the section on Defining Discontinuous Progress, this will seem plausible - the very rapid annihalation caused by a single misaligned AGI going FOOM and the accumulation of ‘you get what you measure’ errors in complex systems that compound seem like totally different concerns.

Despite this, I will show later how the old arguments for discontinuous progress and the new arguments for continuous progress share a lot in common.

I claim that the Bostrom/Yudkowsky argument for an intelligence explosion establishes a sufficient condition for very rapid growth, and the current disagreement is about what happens between now and that point. This should raise our confidence that some basic issues related to AI timelines are resolved. However, the fact that this claim, if true, has not been recognized and that discussion of these issues is still as fragmented as it is should be a cause for concern more generally.

I will now turn to inside-view arguments for discontinuous progress, beginning with the Intelligence explosion, to justify what I have just claimed.

Failed Arguments for Discontinuity

If you think AI progress will be discontinuous, it is generally because you think AI is a special case like Nuclear Weapons where several breakthroughs need to combine to produce a sudden gain in capability, or that one big breakthrough produces nearly all the increase on its own. If you think we will create AGI at all, it is generally because you think it will be hugely economically valuable, so the low-effort case like flight does not apply - if there are ways to produce and deploy slightly worse transformative AIs sooner, they will probably be found.

The arguments for AI being a special case either invoke specific evidence from how current progress in Machine Learning looks or from human evolutionary history, or are conceptual. I believe (along with Paul Christiano) the evidential arguments aren’t that useful, and my conclusion will be that we’re left trying to assess the conceptual arguments about the nature of intelligence, which are hard to judge. I’ll offer some ways to attempt that, but not any definitive answer.

But first, what relevance does the old Intelligence Explosion Hypothesis have to this question - is it an argument for discontinuous progress? No, not on its own.

Recursive self-improvement

People don’t talk about the recursive self-improvement as much as they used to, because since the Machine Learning revolution a full recursive self-improvement process has seemed less necessary to create an AGI that is dramatically superior to humans (by analogy with how gradient descent is able to produce capability gains in current AI). Instead, the focus is more on the general idea of ‘rapid capability gain’. From Chollet vs Yudkowsky:

The basic premise is that, in the near future, a first “seed AI” will be created, with general problem-solving abilities slightly surpassing that of humans. This seed AI would start designing better AIs, initiating a recursive self-improvement loop that would immediately leave human intelligence in the dust, overtaking it by orders of magnitude in a short time.

I agree this is more or less what I meant by “seed AI” when I coined the term back in 1998. Today, nineteen years later, I would talk about a general question of “capability gain” or how the power of a cognitive system scales with increased resources and further optimization. The idea of recursive self-improvement is only one input into the general questions of capability gain; for example, we recently saw some impressively fast scaling of Go-playing ability without anything I’d remotely consider as seed AI being involved.

However, the argument that given a certain level of AI capabilities, the rate of capability gain will be very high doesn’t by itself argue for discontinuity. It does mean that the rate of progress in AI has to increase between now and then, but doesn’t say how it will increase.

There needs to be an initial asymmetry in the situation that means an AI beyond a certain level of sophistication can experience rapid capability gain and one below it experiences the current (fairly unimpressive) capability gains with increased optimization power and resources.

The original ‘intelligence explosion’ argument puts an upper bound or sufficient condition on when we enter a regime of very rapid growth - if we have something ‘above human level’ in all relevant capabilities, it will be capable of improving its capabilities. And we know that at the current level, capability gains with increased optimization are (usually) not too impressive.

The general question has to be asked; will we see a sudden increase in the rate of capability gain somewhere between now and the human level’ where the rate must be very high.

The additional claim needed to establish a discontinuity is that recursive self-improvement suddenly goes from ‘not being possible at all’ (our current situation) to possible, so there is a discontinuity as we enter a new growth mode and the graph abruptly ‘folds back in on itself’.

In Christiano’s graph, the gradient at the right end where highly capable AI is already around is pretty much the same in both scenarios, reflecting the basic recursive self-improvement argument.

Here I have taken a diagram from Superintelligence and added a red curve to represent a fast but continuous takeoff scenario.

In Bostrom’s scenario, there are two key moments that represent discontinuities in rate, though not necessarily in absolute capabilities - the first is that around the ‘human baseline’ - when an AI can complete all cognitive tasks a human can, we enter a new growth mode much faster than the one before because the AI can recursively self-improve. The gradient is fairly constant up until that point. The next discontinuity is at the ‘crossover’ where AI is performing the majority of capability improvement itself.

As in Christiano’s diagram, rates of progress in the red, continuous scenario are very similar to the black scenario after we have superhuman AI, but the difference is that there is a steady acceleration of progress before ‘human level’. This is because before we have AI that is able to accelerate progress to a huge degree, we have AI that is able to accelerate progress to a lesser extent, and so on until we have current AI, which is only slightly able to accelerate growth. Recursive self-improvement, like most other capabilities, does not suddenly go from ‘not possible at all’ to ‘possible’.

The other thing to note is that, since we get substantial acceleration of progress before the ‘human baseline’, the overall timeline is shorter in the red scenario, holding other assumptions about the objective difficulty of AI research constant.

The reason this continuous scenario might not occur is if there is an initial discontinuity which means that we cannot get a particular kind of recursive self-improvement with AIs that are slightly below some level of capability, but can get it with AIs that are slightly above that level.

If AI is in a nuclear-chain reaction like situation where we need to reach a criticality threshold for the rate to suddenly experience a discontinuous jump. We return to the original claim, which we now see needs an independent justification:

some systems “fizzle out” when they try to design a better AI, generating a few improvements before running out of steam, while others are able to autonomously generate more and more improvements

Connecting old and new arguments

With less confidence than the previous section, I think this is a point that most people agree on - that there needs to be an initial discontinuity in the rate of return on cognitive investment, for there to be two qualitatively different growth regimes, for there to be Discontinuous progress.

This also answers MacAskill’s objection that too much has changed in basic assumptions. The old recursive self-improvement argument, by giving a significant condition for fast growth that seems feasible (Human baseline AI), leads naturally to an investigation of what will happen in the course of reaching that fast growth regime. Christiano and other current notions of continuous takeoff are perfectly consistent with the counterfactual claim that, if an already superhuman ‘seed AI’ were dropped into a world empty of other AI, it would undergo recursive self-improvement.

This in itself, in conjunction with other basic philosophical claims like the orthogonality thesis, is sufficient to promote AI alignment to attention. Then, following on from that, we developed different models of how progress will look between now and AGI.

So it is not quite right to say, ‘many of the most prominent people are no longer pushing the Bostrom arguments’. From Paul Christiano’s 80,000 hours interview:

Another thing that’s important to clarify is that I think there’s rough agreement amongst the alignment and safety crowd about what would happen if we did human level AI. That is everyone agrees that at that point, progress has probably exploded and is occurring very quickly, and the main disagreement is about what happens in advance of that. I think I have the view that in advance of that, the world has already changed very substantially.

The above diagram represents our uncertainty - we know the rate of progress now is relatively slow and that when AI capability is at the human baseline, it must be very fast. What remains to be seen is what happens in between.

The remainder of this post is about the areas where there is not much agreement in AI safety - others reasons that there may be a threshold for generality, recursive self-improvement or a signifance to the 'human level'.

Evidence from Evolution

We do have an example of optimization pressure being applied to produce gains in intelligence: human evolution. The historical record certainly looks discontinuous, in that relatively small changes in human brains over relatively short timescales produced dramatic visible changes in our capabilities. However, this is misleading. The very first thing we should understand is that evolution is a continuous process - it cannot redesign brains from scratch.

Evolution was optimizing for fitness, and driving increases in intelligence only indirectly and intermittently by optimizing for winning at social competition. What happened in human evolution is that it briefly switched to optimizing for increased intelligence, and as soon as that happened our intelligence grew very rapidly but continuously.

[If] evolution were selecting primarily or in large part for technological aptitude, then the difference between chimps and humans would suggest that tripling compute and doing a tiny bit of additional fine-tuning can radically expand power, undermining the continuous change story.

But chimp evolution is not primarily selecting for making and using technology, for doing science, or for facilitating cultural accumulation. The task faced by a chimp is largely independent of the abilities that give humans such a huge fitness advantage. It’s not completely independent—the overlap is the only reason that evolution eventually produces humans—but it’s different enough that we should not be surprised if there are simple changes to chimps that would make them much better at designing technology or doing science or accumulating culture.

I have a theory about why this didn't get discussed earlier - it unfortunately sounds similar to the famous bad argument against AGI being an existential risk: the 'intelligence isn't a superpower' argument. From Chollet vs Yudkowsky:

Intelligence is not a superpower; exceptional intelligence does not, on its own, confer you with proportionally exceptional power over your circumstances.

…said the Homo sapiens, surrounded by countless powerful artifacts whose abilities, let alone mechanisms, would be utterly incomprehensible to the organisms of any less intelligent Earthly species.

I worry that in arguing against the claim that general intelligence isn't a meaningful concept or can't be used to compare different animals, some people have been implicitly assuming that evolution has been putting a decent amount of effort into optimizing for general intelligence all along. Alternatively, that arguing for one sounds like another, or that a lot of people have been arguing for both together and haven't distinguished between them.

Claiming that you can meaningfully compare evolved minds on the generality of their intelligence needs to be distinguished from claiming that evolution has been optimizing for general intelligence reasonably hard for a long time, and that consistent pressure ‘pushing up the scale’ hits a point near humans where capabilities suddenly explode despite a constant optimization effort. There is no evidence that evolution was putting roughly constant effort into increasing human intelligence. We could analogize the development of human intelligence to the aircraft case in the last section - where there was relatively little effort put into its development until a sudden burst of activity led to massive gains.

So what can we infer from evolutionary history? We know that human minds can be produced by an incremental and relatively simple optimization process operating over time. Moreover, the difference between ‘produced by an incremental process’ and ‘developed continuously’ is small. If intelligence required the development of a good deal of complex, expedient or detrimental capabilities which were only useful when finally brought together, evolution would not have produced it.

Christiano argues that this is a reason to think progress in AI will be continuous, but this seems to me to be a weak reason. Clearly, there exists a continuous path to general intelligence, but that does not mean it is the easiest path and Christiano’s other argument suggests that the way that we approach AGI will not look much like the route evolution took.

Evolution also suggests that, in some absolute sense, the amount of effort required to produce increases in intelligence is not that large. Especially if you started out with the model that intelligence was being optimized all along, you should update to believing AGI is much easier to create than previously expected.

The Conceptual Arguments

We are left with the difficult to judge conceptual question of whether we should expect a discontinuous jump in capabilities when a set list of AI developments are brought together. Christiano in his original essay just states that there doesn’t seem to be any independent reasons to expect this to be the case. Coming up with any reasons for or against discontinuous progress essentially require us to predict how AGI will work before building it. Rob Besinger told me something similar.

There still remains the question of whether the technological path to "optimizing messy physical environments" (or "science AI", or whatever we want to call it) looks like a small number of "we didn't know how to do this at all, and now we do know how to do this and can suddenly take much better advantage of available compute" events, vs. looking like a large number of individually low-impact events spread out over time.

Rob Besinger also said in one post that MIRI’s reasons for predicting discontinuous takeoff boil down to different ideas about what AGI will be like - suggesting that this constitutes the fundamental disagreement.

MIRI folks tend to have different views from Paul about AGI, some of which imply that AGI is more likely to be novel and dependent on new insights. (Unfair caricature: Imagine two people in the early 20th century who don't have a technical understanding of nuclear physics yet, trying to argue about how powerful a nuclear-chain-reaction-based bomb might be. If one side were to model that kind of bomb as "sort of like TNT 3.0" while the other is modelling it as "sort of like a small Sun", they're likely to disagree about whether nuclear weapons are going to be a small v. large improvement over TNT...)

I suggest we actually try to enumerate the new developments we will need to produce AGI, ones which could arrive discretely in the form of paradigm shifts. We might try to imagine or predict which skills must be combined to reach the ability to do original AI research. Stuart Russell provided a list of these capacities in Human Compatible.

Stuart Russell’s List

- human-like language comprehension

- cumulative learning

- discovering new action sets

- managing its own mental activity

For reference, I’ve included two capabilities we already have that I imagine being on a similar list in 1960

AI Impacts List

- Causal models: Building causal models of the world that are rich, flexible, and explanatory — Lake et al. (2016)9, Marcus (2018)10, Pearl (2018)11

- Compositionality: Exploiting systematic, compositional relations between entities of meaning, both linguistic and conceptual — Fodor and Pylyshyn (1988)12, Marcus (2001)13, Lake and Baroni (2017)14

- Symbolic rules: Learning abstract rules rather than extracting statistical patterns — Marcus (2018)15

- Hierarchical structure: Dealing with hierarchical structure, e.g. that of language — Marcus (2018)16

- Transfer learning: Learning lessons from one task that transfer to other tasks that are similar, or that differ in systematic ways — Marcus (2018)17, Lake et al. (2016)18

- Common sense understanding: Using common sense to understand language and reason about new situations — Brooks (2019)19, Marcus and Davis (2015)20

Note that discontinuities may consist either in sudden increases in capability (e.g. if a sudden breakthrough lets us build AI with full human like cumulative learning), or sudden increases in the rate of improvement (e.g. something that takes us over the purported ‘recursive self-improvement threshold’) or sudden increases in the ability to make use of hardware or knowledge overhang (Suddenly producing an AI with human-like language comprehension, which would be able to read all existing books). Perhaps the disagreement looks like this:

An AI with (e.g.) good perception and object recognition, language comprehension, cumulative learning capability and ability to discover new action sets but a merely adequate or bad ability to manage its mental activity would be (Paul thinks) reasonably capable compared to an AI that is good at all of these things, but (MIRI thinks) it would be much less capable. MIRI has conceptual arguments (to do with the nature of general intelligence) and empirical arguments (comparing human/chimp brains and pragmatic capabilities) in favour of this hypothesis, and Paul thinks the conceptual arguments are too murky and unclear to be persuasive and that the empirical arguments don't show what MIRI thinks they show.

Adjudicating this disagreement is a matter for another post - for now, I will simply note that it does seem like an AI significantly lacking in one of the capabilities on Stuart Russell’s list but proficient in one of the others seems intuitively like it would be much more capable than current AI, but still less capable than very advanced AI. How seriously to take this intuition, I don’t know.

Summary

- The case for continuous progress rests on three claims

- A priori, we expect continuous progress because it is usually possible to do something slightly worse slightly earlier. The historical record confirms this

- Evolution's optimization is too different from the optimization of AI research to be meaningful evidence - if you optimize specifically for usefulness it might appear much earlier and more gradually

- There are no clear conceptual reasons to expect a 'generality threshold' or the sudden (rather than gradual) emergence of the ability to do recursive self-improvement

Relevance to AI Safety

If we have a high degree of confidence in discontinuous progress, we more-or-less know that we’ll get a sudden takeoff where superintelligent AI appears out of nowhere and forms a singleton. On the other hand, if we expect continuous progress then the rate of capability gain is much more difficult to judge. That is already a strong reason to care about whether progress will be continuous or not.

Decisive Strategic Advantage (DSA) leading to Singletons is still possible with continuous progress - we just need a specific reason for a gap to emerge (like a big research program). An example scenario for a decisive strategic advantage leading to a singleton with continuous, relatively fast progress:

At some point early in the transition to much faster innovation rates, the leading AI companies "go quiet." Several of them either get huge investments or are nationalized and given effectively unlimited funding. The world as a whole continues to innovate, and the leading companies benefit from this public research, but they hoard their own innovations to themselves. Meanwhile the benefits of these AI innovations are starting to be felt; all projects have significantly increased (and constantly increasing) rates of innovation. But the fastest increases go to the leading project, which is one year ahead of the second-best project. (This sort of gap is normal for tech projects today, especially the rare massively-funded ones, I think.) Perhaps via a combination of spying, selling, and leaks, that lead narrows to six months midway through the process. But by that time things are moving so quickly that a six months' lead is like a 15-150 year lead during the era of the Industrial Revolution. It's not guaranteed and perhaps still not probable, but at least it's reasonably likely that the leading project will be able to take over the world if it chooses to.

Let’s factor out the question of fast or slow takeoff, and try to compare two AI timelines that are similarly fast in objective time, but one contains a discontinuous leap in capability and the other doesn’t. What are the relevant differences with respect to AI Safety? In the discontinuous scenario, we do not require the classic ‘seed AI’ that recursively self-improves - that scenario is too specific and more useful as a thought experiment. Instead, in the discontinuous scenario it is merely a fact of the matter that at a certain point returns on optimization explode and capability gain becomes very rapid where before it was very slow. In the other case, progress is continuous but fast, though presumably not quite as fast.

Any approach to alignment that relies on a less advanced agent supervising a more advanced agent will probably not work in the discontinuous case, since the difference between agents on one side and another side of the discontinuity would be too great. An iterated approach that relies on groups of less intelligent agents supervising a more intelligent agent could work even in a very fast but continuous takeoff, because even if the process took a small amount of objective time, continuous increments of increased capability would still be possible, and less intelligent agents could supervise more intelligent agents.

Discontinuous takeoff suggests ambitious value learning approaches, while continuous takeoff suggests iterated approaches like IDA.

See my earlier post for a discussion of value learning approaches.

In cases where the takeoff is both slow and continuous, we might expect AI to be an outgrowth of modern ML, particularly deep reinforcement learning, in which case the best approach might be a very narrow approach to AI alignment.

The objective time taken for progress in AI is more significant than whether that progress is continuous or discontinuous, but the presence of discontinuities is significant for two key reasons. First, discontinuities imply much faster objective time. Second, big discontinuities will probably thwart iterative approaches to value learning, requiring one-shot, ambitious approaches.